The second generation takes over

By Dave Duffy

Originally published in issue 200 of BHM, the April/May/June 2025 issue

This is the second time I’ve written the history of Backwoods Home Magazine (BHM). The first was 16 years ago at the end of 2009 on the occasion of the magazine’s 20th year in print. It was a 12-page article whose retelling won’t fit in this space, so if interested you can read it at our free website, backwoodshome.com/history, under the title, Looking back on 20 years of BHM — It all began when I built that cabin. Here’s a brief summary of it:

I founded the magazine in 1989 but its roots began three years before in 1986 when I was 42. I had a crisis of dissatisfaction with my life that resulted in me quitting my job, getting a divorce, selling my house, and retreating from Southern California deep into the Siskiyou Mountains of Northern California along the Oregon border. There I built a cabin by myself, with my little daughter, Annie, age 4, as my helper.

While building and enjoying the stillness of the forest, I thought a lot about what was important in life. I had spent the previous 10 years in the defense industry editing Navy missile systems logistics manuals, getting paid well and doing a good job, but hating it. It felt like the most productive years of my life were being flushed down a drain. After three years, I returned to Southern California and resumed using the only talents I had, which were writing and editing, and started BHM in an effort to do something meaningful with my life.

The cabin I built on Spring Creek. I worked on it for about three years and it became the first step in the creation of Backwoods Home Magazine.

Getting help from friends

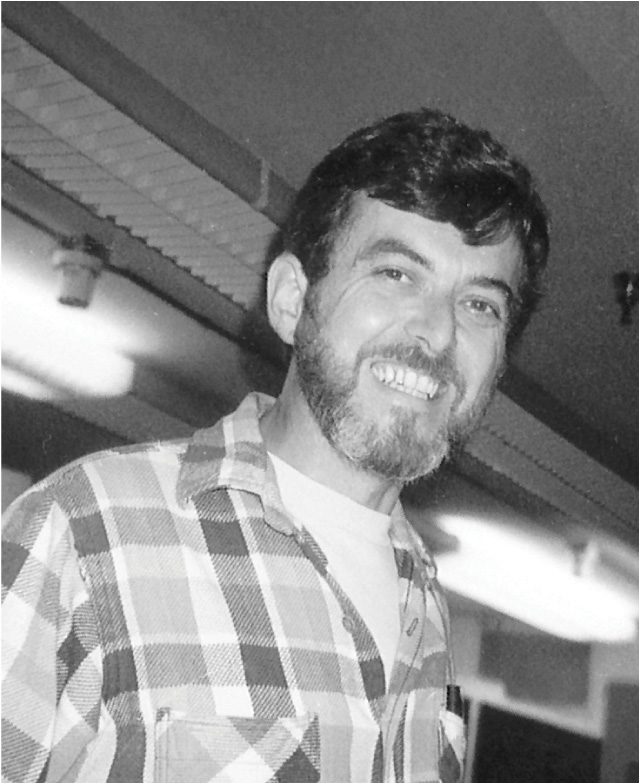

I had worked with Don Childers for four years editing Navy missile systems manuals. He was the best technical illustrator in the industry.

My former co-worker Don Childers, a technical illustrator, drew the art I needed, and John Silveira, a logistician also trapped in a job he hated, helped with the writing. Both worked for free. A surprising number of other former co-workers volunteered their time to help. Former bosses gave me free office space and paid work when I needed it, and co-workers did mundane things like type and sort mail. They liked what I was doing and wanted me to succeed.

My landlord, a computer engineer, gave me free rent and computer assistance in exchange for a few percent of the company. This was the beginning of the personal computer revolution. I bought a clone of the IBM PC, the first truly useful personal computer, and a copy of Ventura Publisher, the first complete desktop publishing system, which I used to launch a magazine I thought could give guidance to people trapped like I had been.

The first issue was somewhat primitive looking but had good articles, most written by me under various pseudonyms. I printed it on credit, and Annie, then 7, and I gave many of them away at a local park.

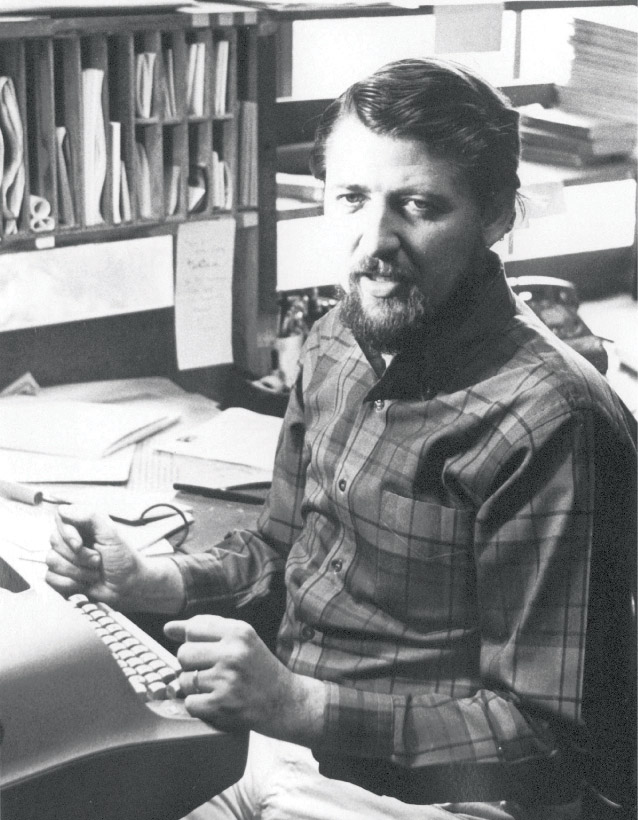

John Silveira was a good writer and researcher who left his Navy logistics job to work for BHM. At both jobs, his desk looked like this.

What a business partner!

After the second issue I met Ilene Myers, a piano playing kindergarten teacher who was as ready for a new adventure as I was. She turned out to be a perfect fit for what I was trying to do and had a work ethic remarkably similar to mine. After a day of teaching little kids, she would come over to my one-room apartment in Ventura, California, and type articles into the night. We got married and she soon took over the magazine’s finances, freeing me up to write and find other good, knowledgeable writers. Knowledgeable is the key word; a lot of writers have no knowledge.

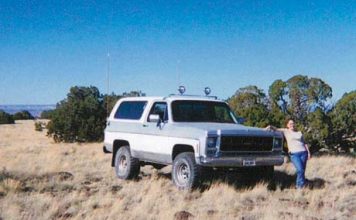

Lenie Duffy in wading boots at the cabin. I met her after the second issue and by sheer luck she turned out to be a perfect match for both me and the magazine.

A note from Shuttleworth

After the fourth issue, the magazine was still relatively primitive looking but it caught the attention of John Shuttleworth, the pioneer publisher who 20 years prior had founded The Mother Earth News (TMEN), a magazine I had never read. I don’t know how he discovered my magazine since he was retired and a recluse, but he gave me important encouragement:

“Someone is always sending me a piece of crap, wanting me to tell ’em what a great job they’re doing. And they ain’t. Their copy is crap, their layouts look like they were done in a blender, their artwork looks first- or second-grade. And besides, there’s absolutely no content in what they’re ‘publishing.’ You ain’t in that class. Your stuff is GOOD. You are doin’ it right!”

I had to go down to the library to read the microfiche on what TMEN was about. It turns out it was similar to BHM, except that 20 years after its founding it had morphed into a publication that had only a few decent articles and lots of ads. Its current state made Shuttleworth angry: “I’m ashamed of what the magazine has become … but damn proud of what it was its first 10 years … when we did the impossible with nothing … So I did my part 10-20 years ago and it’s your turn now.”

Rodney Merrill, Ph.D., was prolific and knowledgeable.

Rodney Merrill, Ph.D., was prolific and knowledgeable.

John Shuttleworth.

John Shuttleworth.

It was the first time an old pro from the publishing business told me what happens to most magazines. They get into financial trouble, get bought at a fire sale, and end up as ad vehicles where the “articles run right into the ads,” as Shuttleworth put it. During the 36 years of BHM’s existence, I would run into many “formerly good” magazines that suffered this fate, and my number one focus was to make sure it didn’t happen to BHM.

Going nationwide

By the sixth issue we had attracted other good writers and BHM had a printing of 6,000 copies on a higher quality press with better paper and sharper type faces, plus the edges of the magazines were cut noticeably straighter. A magazine distributor from the Midwest called me and asked if I could print an extra 40,000 copies so he could put BHM on the national newsstands.

I said “Sure!” without having a clue where I’d get the money for such a large printing. Without hesitation, Lenie took out a loan against her condo.

Going on the newsstands was a big break, and the magazine gradually gained subscribers from there, with Lenie running the business side and me the editorial. The magazine attracted writers who were either knowledgeable about self-reliant skills or involved in homesteading.

Finding good writers

Good writers came along slowly in the beginning. Rodney Merrill was a wonderful early find, and he, Silveira, and I produced most of the articles for the first few issues. Homesteaders Marjorie Burris and Dynah Geissal started writing for us beginning with the fifth through seventh issues, and by the eighth issue Skip Thompsen, a gifted writer and do-it-yourselfer, switched to BHM after TMEN got in financial trouble and ceased publishing for about a year.

I envisioned the magazine as a Renaissance type publication so included poems, both original and classics, an occasional short story, and since Silveira was a mathematician with a love of science and history, he began writing in-depth history and science articles.

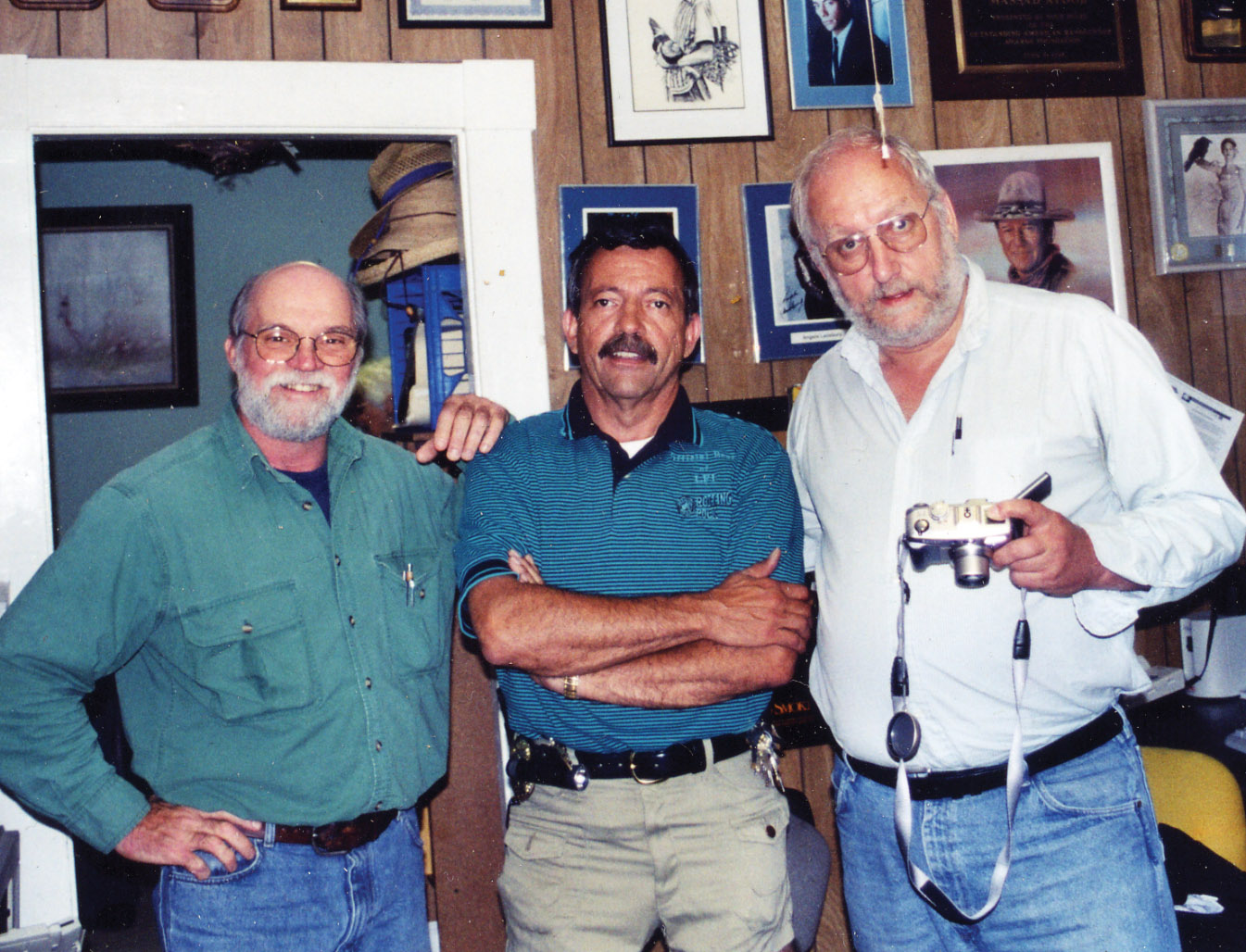

From left: Dave Duffy, Massad Ayoob, John Silveira. John and I had read Mas’s books long before BHM was born. He lived 3,000 miles away in New Hampshire. I sent him a copy of BHM and asked him to write for it. His quick acceptance surprised me, but I quipped to John,“Good writers flock to quality.”

To encourage good writers to keep producing good material, I introduced the practice of paying them as soon as we bought their article, rather than making them wait until it was published, which was common in the magazine industry.

During those early years of the magazine we added three young boys to our family, and I began writing editorials with a libertarian slant that appealed to some people but angered others. Most readers seemed to like my Note from the Publisher, which was a matter-of-fact, sometimes humorous behind-the-scenes account of both the magazine and my family.

By the eighth issue we began buying booth space at renewable energy, environmental, and preparedness shows around the country and that exposed the magazine to a whole new audience of readers, but especially good, knowledgeable writers like Don Fallick, Marilyn Smith Marsh, Martin Harris, Anne Westbrook Dominick, Jeff Fowler, Martin P. Waterman, Vern Modeland, Anita Evangelista, Robert L. Williams, Lucy Shober, and Richard Blunt. They, and many others who joined us in future years, produced quality articles issue after issue.

From left: Patrice Lewis, Jeff Yago, Jackie Clay, Dave Duffy, Annie Duffy, Amy and Joe Alton. All good writers from the old days who still write for us.

Some of the writers needed a good editor, but Silveira and I were proficient at that. It would be another four years (about 20 issues later) that we’d get a writer who needed no editing. That was Massad Ayoob, the renowned firearms author who has been with us ever since. Five issues after Mas, our most popular writer ever, Jackie Clay, found us. With her vast knowledge about every aspect of homesteading, she became our superstar, and still is.

The good years

The magazine became successful with a loyal following, although we never got rich. For about 10 years we had between 15,000 and 20,000 paid subscribers, then gradually increased to about 35,000 paid over the next 10 years, and remained financially healthy with little or no debt. We took ads if they came along but seldom solicited them since we were never big enough to attract serious ad buys.

When we had booths at various trade shows, many enthusiastic subscribers visited us. Some said they drove hundreds of miles to attend the show. At a Denver preparedness show a subscriber walked up to our booth and told me, “I just wanted you to know I flew in from L.A. just to shake your hand.” At one show we offered readers a free book if they would come to the show wearing one of the T-shirts we sold, and they showed up in droves, many wearing homemade T-shirts with “Backwoods Home” written on them.

Our article quality remained consistently high, with both Childers and Silveira leaving their former jobs behind to work full-time for us. They are both now semi-retired like me but Don still paints our covers, John still writes in-depth articles, and I still write columns and articles like this.

The greatest benefit of having our own business like a magazine is that we had the freedom to spend time with our kids and grandkids. Lenie loved that. From back left: Jake, Robby, Sam, Annie. Front left: Tyler, Gavin, Olga, Lenie.

Getting older

Time goes by quickly when you are enjoying life, and we grew older. Although publishing BHM was immensely satisfying for Lenie and me, it was often intense with strict deadlines to meet, many strong writer personalities to deal with, dozens of articles to get correct every issue, and a wide array of other magazine tasks to deal with on a daily basis.

I turned 73 in the spring of 2017, had already undergone triple heart bypass surgery, and was running out of the energy needed to do the job properly. Lenie is 13 years younger than me but she too was tired.

Paper and postage prices had also risen dramatically, straining our finances. Coupled with the free information available on the internet, thousands of small newspapers and magazines had folded. These forces put pressure on us too and led to a rocky financial period in 2017 and 2018.

That’s where the story of this second history of BHM begins.

Closing down the magazine

In Issue #165 (May/June 2017) which was 28 years after BHM was launched, I informed our subscribers in my “Publisher’s Note” that the magazine would go digital-only at the end of the year. I simultaneously announced it with emails to the subscribers for whom we had email addresses, and on Facebook, where a half million people “Liked” our page.

The outpouring of grief from readers was enormous. We got hundreds of emails and letters, and it was an emotional ride for me rereading them for this article. Here are some excerpts:

— “I’m in tears as I read your words …”

— “Your announcement took my breath away …”

— “That awful sound you hear is me yelling my frustration at your awful message …”

— “This breaks my heart. So much. I feel like I have grown up with Dave and Annie and Jackie Clay …”

— “I understand, but still it is heart-wrenching to lose Backwoods Home …”

— “I must say I did literally shed a tear …”

— “Wow! I understand, but I feel like an old friend has told me they have terminal cancer …”

— “We will be in mourning for years …”

— “I just read about BHM ceasing publication in December and I’m feeling heartsick …”

— “I am sad to hear this. This is the only magazine I subscribe to …”

— “We love you. It’s been awesome. Thanks for all the years of outstanding magazines …”

— “How heart breaking. I love your magazine …”

— “This makes me sad. My husband watches the mailbox like a child for our copy …”

— “Thanks for all the years, knowledge, and joy you have brought …”

— “Sad to see this but thank you for all the priceless information you have provided for so long …”

— “Not many would have the integrity to announce such a thing in advance. Fits perfectly with what I have come to expect over the years …”

— “Backwoods Home Magazine literally changed my life … I was 38 when I began reading, and am 64 now … I know your daughter and one of your sons is going to keep the Backwoods Home legacy alive …”

The last excerpt was prophetic.

Selling was not an option

The decision to go “digital only,” which most subscribers assumed was the prelude to closing down completely, was made because none of our four children wanted to assume responsibility for publishing it, and we could not find an acceptable buyer.

Sam, our youngest at 22, and Annie, the oldest at 35, were in the process of taking Self-Reliance, our 6-year-old digital magazine on Amazon’s Kindle platform, into the print world. It was their try at starting their own business, but after two years their prospects were uncertain. Historically, 90 percent of new magazines fail between their first and third years.

I think BHM seemed a daunting task to them. They had seen us struggle financially the previous year, cutting the magazine’s size from our usual 100 pages to 84 pages to save on print and postage costs. Plus, Annie had her hands full tending her farm and raising her three children, and Sam was still in college.

Our talks with a potential buyer, Swift Communications, which owned many newspapers and magazines across the country, was shocking. I saw BHM as an influential magazine dominating the homesteading market, but they saw it as a small publication with little financial value because it had only 40,000 subscribers to whom they could sell products. Even though I understood that BHM’s formula of using good articles to attract subscriber dollars was the opposite of most magazines, I was amazed they valued us so low.

Only a few years previous, Swift had paid more than a million dollars for Countryside, the magazine most similar to BHM and owned by the Belanger family. Countryside’s publisher Dave Belanger and I became friends and we talked often about our different management philosophies. He thought editorial content was unimportant, and he fattened Countryside’s subscriber numbers with sophisticated promotion campaigns for what he intended to be a good payday for the magazine’s eventual sale.

He said Mother Earth News went even further to grow their subscriber numbers for advertisers, often giving the magazine away with a $10 subscription price that didn’t cover costs. Both magazines are now owned by Ogden Publications and are basically ad vehicles.

Regardless, Lenie and I didn’t like the idea of selling our readers to a magazine conglomerate as advertising fodder. We knew many of them personally from the tradeshows, and many had traveled hundreds of miles to visit our Oregon office.

So instead of selling, we opted to close. We announced the closure early enough so we could fulfill most subscriptions, and we paid off the rest, mostly with product but some with money.

After our one year as a digital-only magazine, we were broke because we had no subscription revenue coming in. We were hoping to sell our anthology books as a retirement job but that business was slow to take off. That’s when the IRS told us BHM owed them $150,000 in deferred taxes.

Lisa and the Dennings

We had three superb employees left to help us wind down the magazine:

Lisa Nourse, who has held the critical job of editorial coordinator for the past 24 years, dealt with writers.

Rhoda Denning was the voice on the telephone for thousands of subscribers who contacted the office during her 15 years with us. She handled the tricky task of negotiating with long-term subscribers to compensate them for the portions of their subscriptions that could not be fulfilled. She is now retired.

Rhoda Denning, left, proofed articles and was the main telephone contact with subscribers for 15 years. Lisa Nourse, middle, is in her third decade as the main contact for writers, and Jessie Denning, Rhoda’s daughter, was an important managing editor for five years during BHM’s transition to digital-only for one year, then back again to print.

Jessie Denning, Rhoda’s daughter, was the managing editor from 2014 to 2019, maintaining the quality while we struggled with finances. Jessie was a good editor and smart. She had a knack for quickly learning computer programs, which I had her do to modernize our operations and save money. She now runs her own website design business (denningprint.com) with knowledge learned while BHM’s editor.

The apple tree conversation

When the final digital issue was published in November of 2018, we prepared to close down BHM entirely. The family was getting ready for our annual apple-picking adventure at Annie’s farm where we’d climb her huge wild apple tree across the Marys River and glean it.

Sam, who had turned 23, said to me, “Dad, I don’t think you should close BHM completely.” His older brother, Jake, interjected that maybe Sam should try to bring it back to print since he was having some success with Self-Reliance. By that time the kids had gained just over 9,000 paid subscribers for Self-Reliance and had gotten more confident.

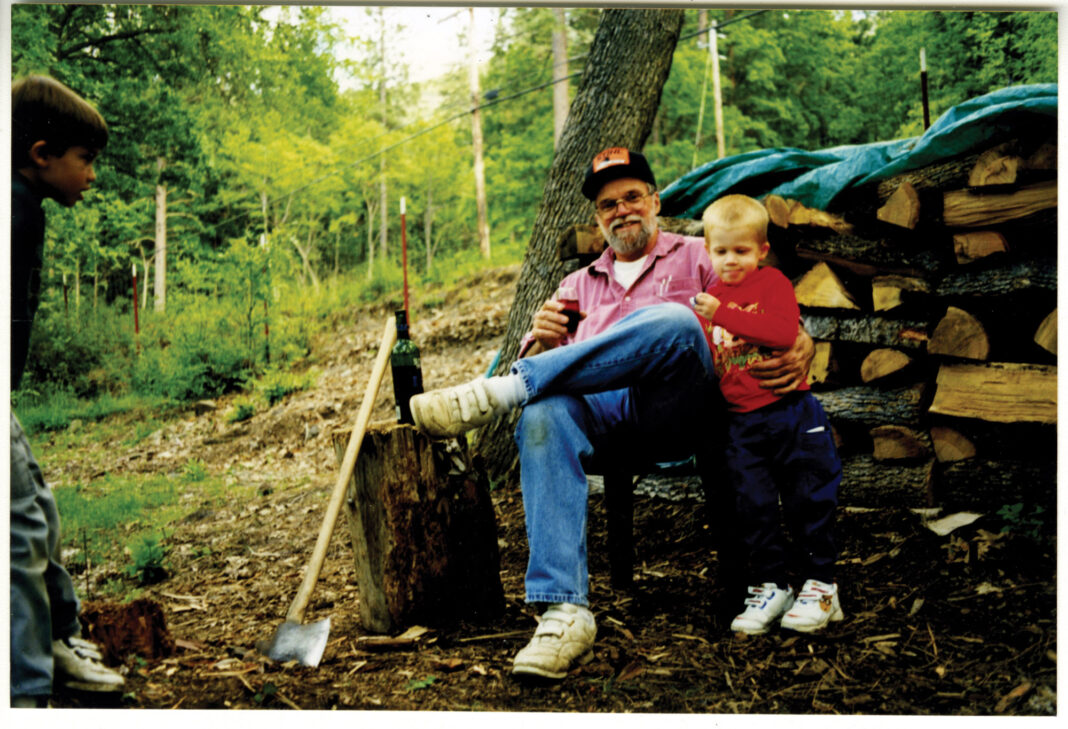

We discussed it while Sam was high up in the tree and me on the ground catching apples, hollering back and forth. A week later, Lenie and I sold it to Sam and Annie for $2. We threw in the company truck for another dollar.

Sam and I discussed the sale of BHM in Annie’s giant wild apple tree, with him up top and me on the ground. Our family gleaned it every year. By the time the apples were all picked, we agreed he and Annie would buy the magazine for $2.

It was a great relief for Lenie and me. It meant we didn’t have to pull the trigger on something we poured so much of our lives into. We readily agreed to write articles, help edit, and assist wherever needed.

Two months later they resurrected BHM as a print magazine, so that the final digital-only issue was followed by a print issue without the magazine missing an issue. The response from our former readership was huge. They resubscribed in droves, with many “thanks for saving the magazine” type of comments scribbled on their renewal forms.

Sam the problem solver

Although Annie was the natural writer and editor, Sam turned out to be the one who saved the day with his business skills, some learned from his classes at Oregon State University, but most learned on the job. He had a good understanding of computer programs and social media, and an ability to isolate and solve problems. He dropped out of college to run the magazine.

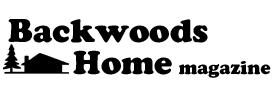

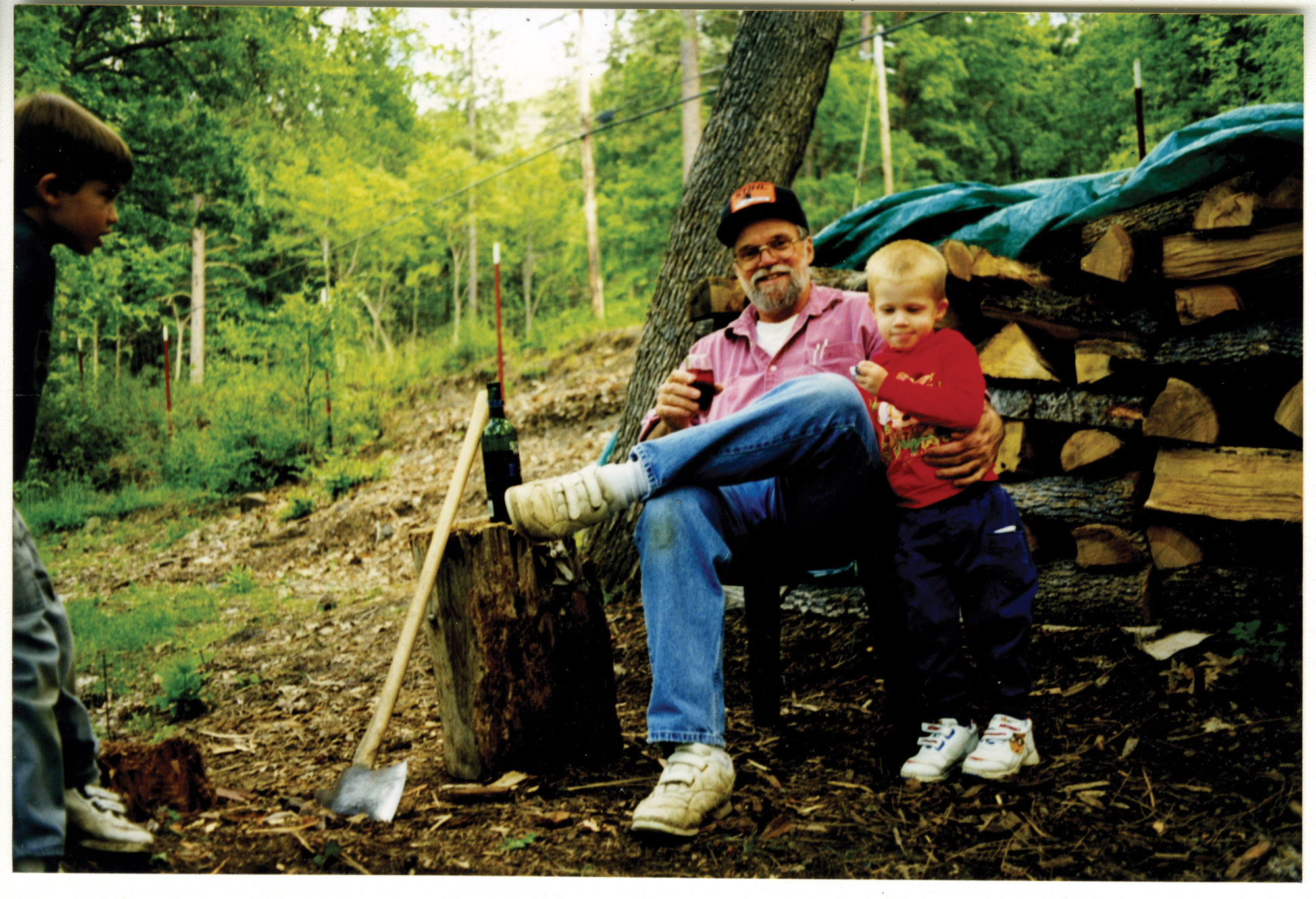

Early get-together of the former and future BHM publishers. Dave Duffy, left, and Sam Duffy, age 3, right.

Sam was five years away from being born when I founded BHM, but I think he was born a capitalist. He was making money from his brownie stands in front of the magazine’s office building in Gold Beach, Oregon, from about the age of 7.

In 2011, at age 16 and still in high school, he assumed responsibility for uploading the magazine’s digital magazine, Self-Reliance, and the digital version of BHM, on Amazon’s Kindle platform.

By the time he and Annie took over BHM, he was proficient with all its computer programs and immediately set out to improve them, rewriting the code for the database and redesigning our huge website. Lenie and I had always had to employ an IT (information technology) guy and a webmaster, and they were expensive. Sam assumed both jobs.

Since he had natural artistic talent he also assumed the job of laying out the magazine pages. In a magazine, presentation is important. As Shuttleworth noted, the layout can’t look like it was done in a blender.

In 2021 he hired his brother Jake as an additional editor to Annie. Both had natural ability as writers and editors. He also hired two more young promising college grads with English degrees, Amanda Green and Sarah Kendall, and let them learn on the job. They are editors now. More recently, Victoria McGloughlin joined the staff who helps with proofreading. They’ve all worked out great.

Editors are plugged into a sophisticated system of editing and proofing that Sam designed and coded. He made me the “verdict” guy, whereby I read the editors’ ratings for an article, along with their reasons, then decide whether the article is a “buy” or “rejection.” It’s an easy job compared to having to read the whole article. The only time I do that is when there is editor disagreement or when the ratings are marginal. I make fewer “buy” mistakes than I made in the past.

Annie Duffy eventually sold her portion of the magazine to Sam and became a full-time farmer. She is still an editor.

Understanding the finances

But Sam’s most important asset as publisher was his understanding of finances. The first major change he made was to increase the magazine’s length from 84 pages back to its traditional 100 pages. But he cut the costs of printing and postage by changing the magazine from a bi-monthly to a quarterly, just like Self-Reliance.

He reasoned that former subscribers would accept cutting their number of issues from six to four a year if it meant saving BHM as a print magazine. If they wanted more magazines per year, they could also subscribe to Self-Reliance, the next best thing to a clone of BHM, except it has no gun articles or my conservative editorials. We’ve never gotten a single letter of complaint from readers about getting fewer issues per year.

His redesigned subscriber database allows the eight office staff who answer the phones to quickly update subscriber details when they call in or when they enter data from mailings.

He’s taken full advantage of advertising on Facebook, something people had been telling me to do for years but I couldn’t quite figure it out. He set up an auto-renew system with incentives, and about 70 percent of Facebook respondents signed up for it. Auto-renew saves a bundle of money on renewal mailings.

Lately he’s been making deals with about a dozen YouTubers to help drive subscriptions, and that is working well. At the dawn of the internet more than 30 years ago, when BHM had a website but CNN still did not, I predicted in an editorial that the internet would naturally allow excellence and truth to rise to the top, but I still don’t understand social media.

Sam does things Lenie and I couldn’t do, not just because we had not imagined them but because we lacked the knowledge and computer savvy to implement the ideas even if we had imagined them.

In the 28 years Lenie and I had stewardship of BHM, the highest paid subscriber number we achieved was 37,000, with another 5,000 Kindle subscribers. Sam, now finishing his sixth year, has 150,000 paid subscribers for BHM, most on auto-renew, with another 60,000 paid subscribers for Self-Reliance. Amazon has since closed its Kindle platform for magazines.

I occasionally ask him if he’s going to sell ads since he now has the numbers to attract advertisers. His answer: “We have a few, but ads take up too much space. I’d rather focus on content.”

Sam likes working with Don as much as I do. He draws very fast, and he will quickly erase a pencil sketch and redraw what you want. Then he’ll paint it. He’s done most of our covers, beginning with the first, and a lot of the inside art.

Don sometimes flies from his home in Colorado to work with us at our office in Oregon. Here he celebrates his 93rd birthday at our office in 2023.

Keeping the old folks

Lenie and I still write our columns, she with “Lenie in the kitchen” and me with “My View” for BHM and “Perspective” for Self-Reliance, but I keep reminding Sam he’s got to get new columnists for his younger demographic. Lenie also continues her role on the business side. She no longer is responsible for how the money to operate is generated, but she still compiles the income and outgo numbers for the accountant and does special projects like creating new books for sale.

The quality of BHM and Self-Reliance are as high as they’ve ever been. Several of our best writers from the old days have died, while writers like me, Silveira, Jackie, Mas, Dorothy Ainsworth, and Jeff Yago are pushing 80. Childers is now 94. But Sam has developed a new flock of writers who are just as good and knowledgeable as we and our writers were.

So BHM has been saved and continues as a print magazine, and its financial position is stronger than it has ever been in its 36-year history. It’s still “content driven” with very few ads, and it has a young publisher who knows what he’s doing. I’m pretty happy with the way things worked out.

The current editorial crew, from left: Victoria McGloughlin, Lenie Duffy, Jake Duffy, Dave Duffy, Sam Duffy, Annie Duffy, Sarah Kendall, Amanda Green. Lisa Nourse, our editorial coordinator, is not shown. She attends our weekly editorial meetings via Zoom since she lives in a different Oregon city.