By John Silveira (aka O.E. MacDougal)

May/June 2017 Backwoods Home

The greatest inventions in history are the ones we now take for granted. Fire and the wheel-axle combination are among them. If we weren’t taught in school how they revolutionized human existence, we wouldn’t even think about them now, and if you didn’t learn it in school, you probably don’t think about them ever. But there are other inventions that, in their day, were astounding, but just about everyone takes them for granted today.

Paper

For instance, yesterday, after jotting some notes on a piece of paper, I didn’t like the way they were coming out so crumpled the sheet into a ball, tossed it, and as it traveled in an arc toward the trash can, it dawned on me I was discarding a specimen of one of the greatest inventions in history. Paper!

Paper is one of the cornerstones of modern civilization. Without it, we would have advanced little beyond the Middle Ages. And paper, coupled with the printing press, is probably the greatest invention in the last 2,000 years.

Historians are pretty sure writing itself was invented by “accountants” in the ancient Middle East. The earliest kings and merchants needed ways to keep track of their assets and trades, and one of the earliest ways they recorded these things was to impress figures that represented cattle, wheat, sheep, etc. onto clay tablets that were then baked in kilns to harden so as to preserve the information. Today, shattered pieces of these tablets are regularly found by archeologists when they dig up ancient cities. Record keeping on clay tablets was only for the wealthy, however, and works of literature were rarely recorded. The mass of humanity was illiterate.

Ancient literature was almost always orally transmitted. Homer, reputed author of the two of history’s greatest epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey, was a blind and likely illiterate poet. If tradition is to be accepted, he composed his works as early as 800 BC. After that, they were memorized by various orators, almost always men, and almost all of whom were themselves illiterate, who recited them to audiences who were also illiterate. Neither of these masterpieces was written down until as late as 675 BC. Otherwise, by now they would be lost to us forever. And there’s no telling how many other pieces of literature have been lost due to the lack of paper.

The Chinese did, however, prior to the invention of paper, write a few things on bamboo, which was bulky and cumbersome, so was heard by limited audiences. They also wrote on silk, but silk was expensive.

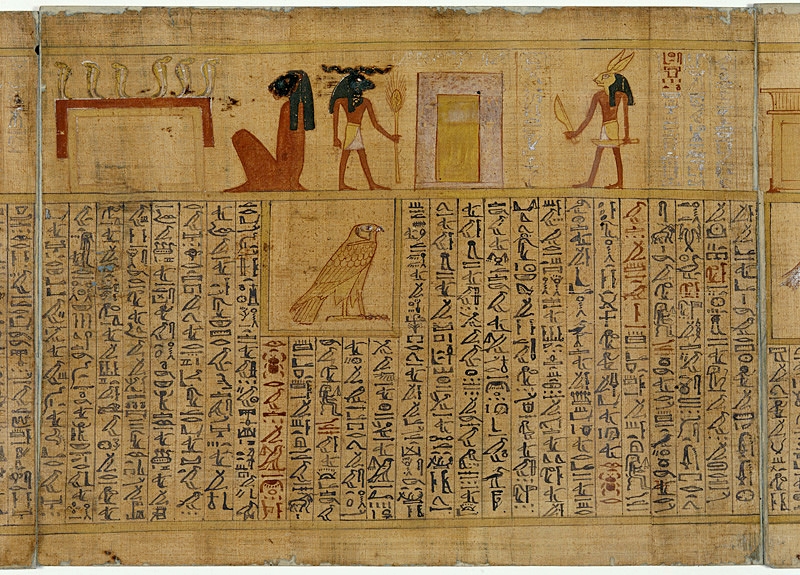

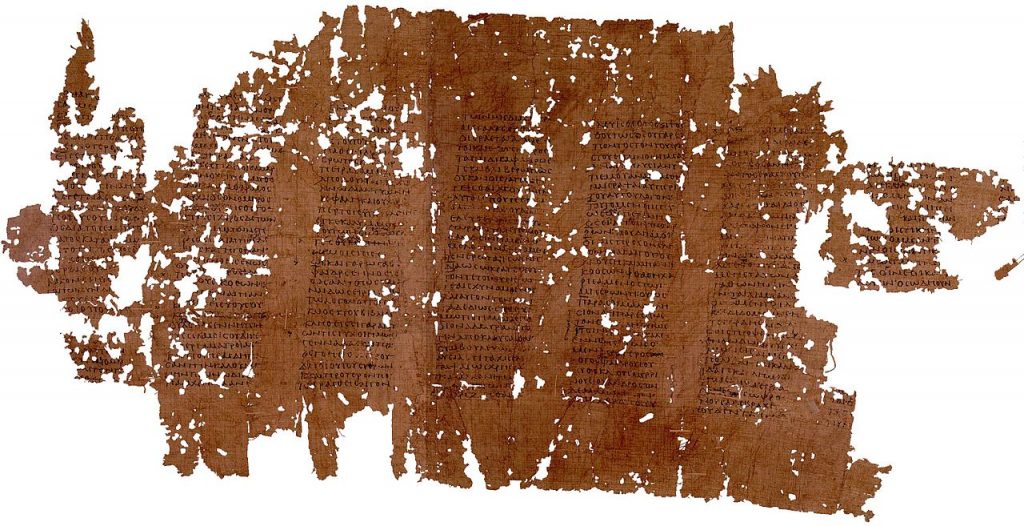

In Egypt and the Mediterranean, papyrus had long been used, but it wasn’t widely available. It was fragile and expensive. What was recorded on papyrus usually wound up in libraries, such as the one in Alexandria, Egypt, which famously burned down more than once and because the scrolls in that library were often one-of-a-kind copies, the information on them was lost with each blaze.

Further north, in Europe, parchment and vellum, made from animal skins, primarily sheep, goats, and calves, were used.

Then Chinese invented paper, perhaps as early as 100 BC, making it from the fibers that comprised the inner bark of the mulberry tree. Though they didn’t turn the production of paper into a real industry until sometime between the 1st and 3rd centuries AD, they knew they had a good thing and kept the process for making it a state secret for several centuries. Other cultures, even after being given sheets of paper, had no idea how it was made. But like the secrets for many of their other inventions, such as woven silk and gunpowder, the process for making paper was eventually snuck out of China.

Paper reached India by the 5th century AD, Korea and Japan by the 7th century, and the Islamic world by 800 AD. Around 1250 AD, the process for making it made its way to Italy and from there spread throughout Europe. Though its use still wasn’t widespread, the recording of data and literature became easier. But paper still didn’t radically change the ordinary person’s life until …

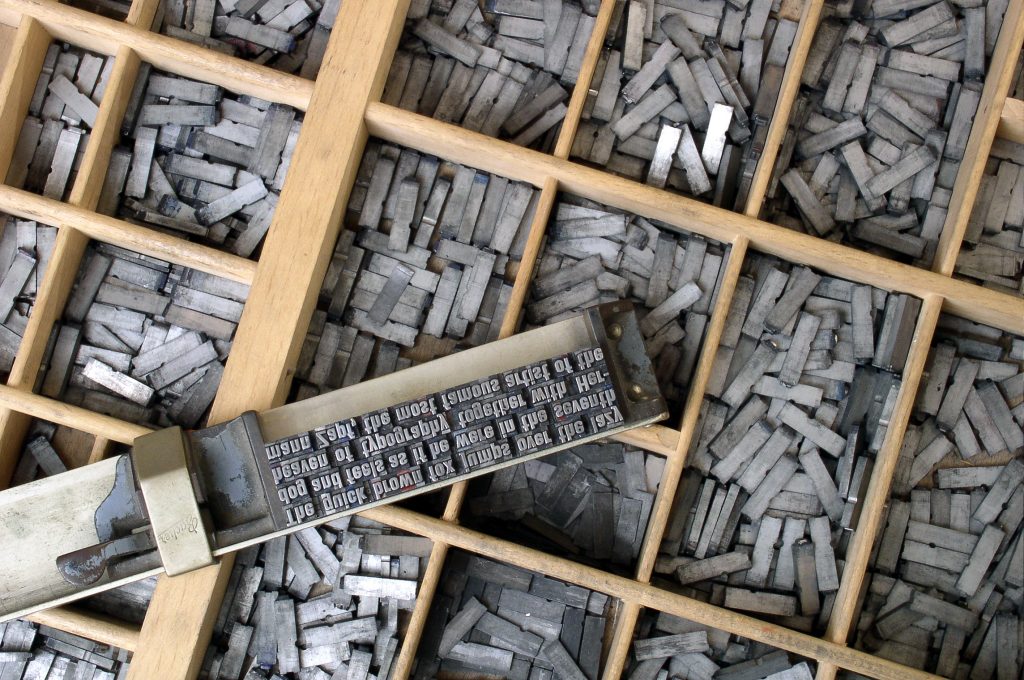

Printing Press

Then came the printing press. The Chinese invented the first printing press with “movable type” in the 11th century AD. But their written language uses several thousand characters called logograms and printing documents involved having thousands of these characters, which were made out of wood or ceramic. This made printing expensive and inefficient. Because of this, it had little impact on China. But in 1450 AD, a German, Johannes Gutenberg, made his own printing press. This one used metallic, movable type, and because his press required type only for an alphabet of 26 characters and punctuation marks, it made mass printing possible and created an explosion of information not seen before. Books and pamphlets started proliferating. Libraries, even personal libraries, were possible. Literacy gradually spread. Gutenberg’s press would change the world, but it wouldn’t have happened had not the Chinese invented paper, first. Together, paper and the press led to an explosion of knowledge and, though it took time, the masses began to get educated.

Without paper and the press, there’d have been no Renaissance, no revolution in science because the exchange of ideas would have been restricted to the spoken word or laboriously hand-printed documents. Some have called paper the greatest invention since fire and, when coupled with the printing press, it probably is.

By the way, the Chinese found other ways to use paper. They used it to make kites, playing cards, folding fans and, ultimately, they invented the world’s first toilet paper. That last one happened around 1350 AD, but TP didn’t catch on in the West until centuries later. Let’s not think about what people did until then.

Paper is not likely to go away, but some of its uses are in decline as electronic words have, in many instances, replaced it. Newspapers, magazines, and printed books are gradually disappearing and though they probably won’t completely disappear, one of history’s greatest inventions is making way for another great invention — the computer.

Canned Food

Since ancient times, food provisions were the greatest limiting factor in determining military campaigns. Armies had to eat. This pretty much created a season for war. Military campaigns usually took place after the harvest was in and before new crops had to be planted in the spring. Napoleon famously said, “An army marches on its stomach.” It’s been that way for millennia.

So, how do you feed an army? During the Napoleonic Wars, the French government offered a cash reward to anyone who could discover an economical method for preserving large amounts of food. Enter Nicolas Appert, a Frenchman. He observed that food that was cooked and placed in sealed containers didn’t spoil—as long as the integrity of the seal was maintained. With that in mind, he devised a method of canning food to preserve it. The French government paid him the prize. However, mass producing and distributing of canned food was not perfected in time to save the French army and Napoleon lost his final battles. But Appert’s invention lived on.

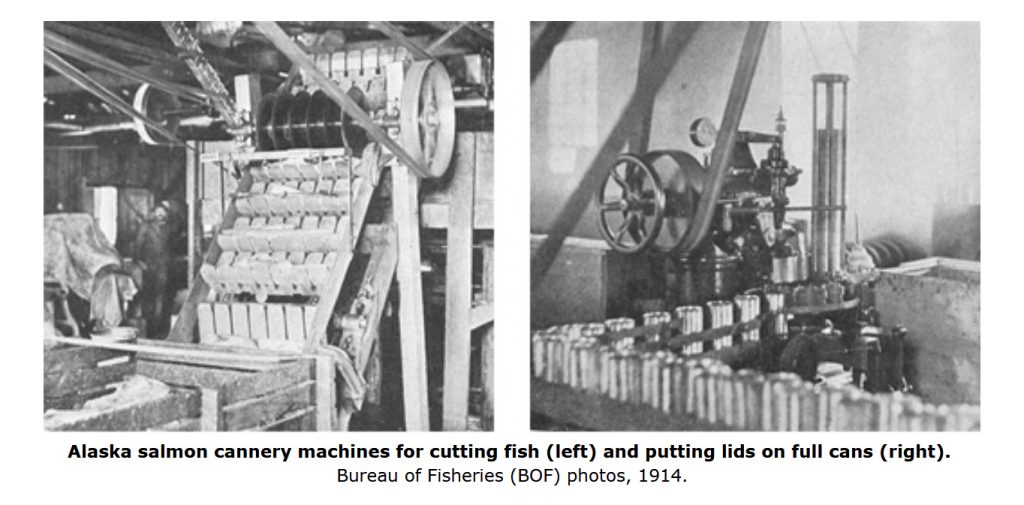

In its early days, canning still had issues. The early metal cans that were used were sealed with lead solder. Lead turned out to be a dangerous contaminant. Also, the cost of canning was still prohibitive and was too expensive for feeding the masses. But this would all change because of more 19th century wars. Armies in both Europe and the United States had large numbers of troops that had to be fed. A well-fed army could make the difference between victory and defeat. This provided the incentive to perfect the mass production of canned food. Manufacturing innovations also drove the cost down. By the late 19th century, not only were military units living on canned goods, but they began to appear in markets and in homes both in Europe and the United States,

In its early days, canning still had issues. The early metal cans that were used were sealed with lead solder. Lead turned out to be a dangerous contaminant. Also, the cost of canning was still prohibitive and was too expensive for feeding the masses. But this would all change because of more 19th century wars. Armies in both Europe and the United States had large numbers of troops that had to be fed. A well-fed army could make the difference between victory and defeat. This provided the incentive to perfect the mass production of canned food. Manufacturing innovations also drove the cost down. By the late 19th century, not only were military units living on canned goods, but they began to appear in markets and in homes both in Europe and the United States,

Home canning, however, didn’t become common until an American, John Mason, invented a glass jar with a metal lid that was suitable for canning at home—hence the name, “Mason jar.” Initially, the jars were so expensive only the wealthy could afford to can at home. But as the price of jars and other canning equipment dropped, more and more home canning took place until, finally, it became a preferred method of food preservation on American farms. But in the 20th century, the proliferation of industrial canned goods all but wiped out home canning. It is only recently that home canning is making a comeback, especially among self-reliant types.

Today, you can walk into any large supermarket and find hundreds of thousands of cans of food, all inexpensive, nutritious, and safe to eat. They are so common that no one I know stops to think that just over 200 years ago, there wasn’t a can of food anywhere on the planet.