|

|

| Issue #138 • November/December, 2012 |

When we eat, we incorporate all of our senses (sight, touch, hearing, taste, and smell) to help us make a general determination about the food in front of us. But taste is the most important in helping us decide if a food is appealing. My favorite cook, the beloved French chef, Julia Child, taught us that, although cooking to satisfy taste is definitely an art, developing savory flavors in prepared foods is a science.

Many years ago, cooks in Asia discovered that, along with the four basic human tastes of sweet, salt, sour, and bitter that we traditionally recognize here in the West, there is also a fifth “taste.” The Japanese call it umami, which translates as “meaty or broth-like” flavor.

Since the 1980s, western scientists have come to recognize umami as a legitimate taste. It is activated by a common amino acid known as glutamate, found in tomatoes, fish, Parmesan cheese, soy sauce, mushrooms, and other natural foods. When glutamate is combined with inosinate, a disodium salt found in foods like anchovies, dried mushrooms, bonito flakes, pork, and beef, the synergistic effect of umami develops. If all of this sounds a little gourmet-like and scientific, then consider doing this: The next time you eat a cheeseburger, pay attention to your taste buds, and you will discover a singular complex and pleasing flavor that is not sweet, sour, salty, or bitter. The combination of glutamates from the cheese and the inosinate from the meat reward you with that umami taste.

The processed food industry takes advantage of this phenomenon and often combines monosodium glutamate (MSG), a processed form of glutamate, with two disodium salts, inosinate and guanylate, and they incorporate this “umami cocktail” into their recipes to improve flavor that is usually lost during processing. If these names sound foreign or strange, read the ingredients list on a can of Campbell’s Chunky Chicken Noodle Soup; you’re going to find them there and I am willing to bet that additives like these are more common in processed foods like potato chips and other snack foods than you probably realized.

Chiles for the chili seasoning

During the past two years I have experimented with this umami principle by combining small amounts of glutamate-rich ingredients with others containing inosinate. I then added these combinations to several standard Blunt family dinner foods including vegetable soup, chicken pot pie, and beef stew. The umami activators I add to these recipes include anchovies, soy sauce, and other items I listed above, in both dried and fresh forms. To each recipe I add a different combination of these ingredients without altering the recipe’s original ingredients or changing their amounts. The results of these experiments were promising so I decided to apply the principle to one of the most complex combination of flavors on the planet beef chili. A close look at almost any meat-based chili recipe is going to reveal that it is a classic umami stew because it will incorporate many of the ingredients I’ve listed above.

Several years ago I read Frank Tolbert’s book, A Bowl of Red, and became fascinated with the passionate following this dish has. Also, every year I check the International Chili Championship website looking for new ideas and inspiration from these executive chefs of chili, and every year I am surprised to find that none of the winning recipes contain any of my most cherished ingredients: fresh vegetables, fresh and dried whole chile peppers, or fresh garlic. Instead, each recipe incorporates a combination of supermarket or mail-order chili powders along with MSG-ladened flavor boosters like packets of Sazón Goya, dried beef, or chicken granules. All of these championship recipes are very similar, which is more of a testimony to the restrictive rules of the contest than of the culinary skills of the contestants.

The chili recipe I offer here would be a first line candidate for disqualification because in the chili cook-offs, fresh onions, fresh chile peppers, fresh garlic, and beans are not allowed. So my chili breaks all their rules.

Though I have made chili before, I began seriously dabbling with various chili recipes about a year ago. During this time I have collected about 60 recipes from various sources. I have included, in the formula I’m presenting here, some of the better ideas for ingredients that I discovered in these recipes and I am going to share with you my reasons for using these selected ingredients, along with the method for incorporating them into my formula, to help you make a better chili.

Ingredients for chili

Making a better chili seasoning

All of the recipes I reviewed from the Chili Championship incorporated a variety of commercial chili powders. Some incorporated as many as four different kinds. I have always avoided using these commercial varieties because of their sandy texture, which results from grinding the seeds and stems together with the chile flesh. I don’t believe all commercial chili powders are ground this way, but there are far too many varieties on the market for me to sample them all and determine which ones are ground to my satisfaction and which are not. Hence, I decided that my best option was to assemble my own.

The most important taste component in a bowl of chili is the chile pepper. When using chiles in any recipe that will be cooked, it is important to consider more than their incendiary punch. Each variety has its own unique flavor and heat profile. Twelve years ago I wrote a piece on chili for BHM. I included a custom-made chili powder in that article. After looking at that old formula, I decided to make some changes that would make it a better fit for this recipe.

Chili burn is the main subject at the dinner table when this stew is served. Two of the dried pepper varieties I chose for that old formula are known for their taste rather than their heat (cascabel and New Mexican). The third pepper in that old recipe, de árbol, is a popular chile with a mellow, earthy taste, and medium heat.

For this formula I wanted dried chiles with low heat and rich, mellow taste. Ancho (the poblano chile pepper when it is dried), pastille, and mulato (the dried, smoked poblano chile pepper) are all good choices. I chose the ancho because it is available in many stores, both whole and ground. As a complement to this mild chile pepper I decided that a quality Hungarian sweet paprika was the best choice, to add a fruity and earthy taste-balance to the formula. However, finding a variety of Hungarian paprika that had the flavor profile I wanted was a problem. The very best sweet Hungarian paprika I found is only available online from Spice House (www.thespicehouse.com). This is a worthwhile purchase for me since I often prepare beef, vegetable, and chicken dishes that require a full-flavored, sweet Hungarian paprika. If you feel that special ordering paprika is not necessary for this recipe, McCormick paprika, found in supermarkets, is a respectable substitute.

I eliminated aromatic spices like allspice and clove from my chili powder because I feel that they mute the basic chili flavor I am looking for.

To round off the flavor of this spice mixture, I included spices that, by tradition, are used to flavor a good chili: oregano, cumin, coriander, and powdered garlic.

Making the umami cocktail

Multipurpose chili seasoning: (makes about 1 cup)

4 oz. ancho peppers, stems and seeds removed, flesh torn into ¾-inch pieces

2 Tbsp. sweet Hungarian paprika

2 Tbsp. dried oregano leaves

2 Tbsp. cumin seed, toasted and ground

2 Tbsp. coriander seed, toasted and ground

2 tsp. garlic powder

If toasting and grinding the ancho peppers is not possible, specialty stores and many supermarkets sell pure ancho powder. It is best used right from the package without toasting.

Method:

1. Toast the ancho chiles in a heavy-bottom skillet over medium-high heat until fragrant. Stir the peppers frequently to prevent burning.

2. Remove the peppers from the pan and set them aside until cool.

3. Grind the peppers to a fine powder in a spice mill or coffee grinder dedicated as a spice grinder.

4. Combine all ingredients and mix until well blended. Pack in a container with a tight-sealing lid and store in the freezer.

By the way, I also use this chili seasoning as a barbeque rub for chicken, beef, pork, fresh salmon and trout, and grilled vegetables. It isn’t just for making a pot of chili.

Trim and dice chuck

The other chili ingredients

Beans: Ignoring the norms of the championship chili cook-off, I decided to add beans to this chili. I have used both dried and canned beans in this stew and I feel the dried beans are the best choice. When prepared properly, dried beans are not only a great food served alone, they are also an excellent complement to any stew, especially chili. They develop lots of flavor when cooked in the chili, and brining them (i.e., processing them in salted water) for a short time before adding them to the chili allows them to form creamy interiors without ruptured skins.

Peppers: I omitted hot chile peppers from the seasoning to give myself more latitude with the heat profile of the finished stew. To give the finished stew an adjustable heat level, I included a dried chile with moderate heat and one fresh variety with a high heat. These can be introduced into the chili, according to taste, during final preparation. With this combination of three dried pepper varieties and one fresh, the possible combinations are almost endless.

My favorite fresh chiles are jalapeño and serrano. Both add bright flavor to many dishes. But buying fresh chile peppers for their heat value can be a hit-or-miss proposition. Chiles get their heat from chemical compounds called capsaicinoids; the most familiar of these is capsaicin. The hottest chiles are those grown under stress, like those growing in high desert regions. But when you are standing in the produce section of your local grocery store, trying to determine which chile pepper will best suit your needs, be aware that there is no way to determine if a chile has lived a stressed or charmed life. So, what do we do? Both the jalapeño and serrano have bright, clean flavor with the serrano having a more consistent higher heat value. I grow both jalapeño and serrano peppers in my garden. With careful watering I can usually control growing conditions to maximize their heat value. I also chose the serranos because they can be blanched and frozen, and what I don’t use during the growing season, I can use during winter months. Blanching preserves the pepper’s bright flavor and heat. I also added the dried de árbol pepper to the recipe for a reliable and easily adjustable source of heat.

Thickener: To thicken the chili and add an additional subtle layer of flavor I use a small amount of masa harina as a thickener. I do a lot of baking with this limed corn flour and always have a four-pound bag on hand. However, buying a bag of this flour may not be practical for the small amount called for in this recipe, so regular or fine-ground cornmeal is a good alternative.

Browning chuck

Liquids: I use low-sodium chicken broth because all of the canned beef broths that I sampled had an unpleasant tinny taste. A quality chicken broth can be used in any type of stew or braise without any ill effect. In this formula I use Swanson Certified Organic chicken broth because it has a very straightforward and honest flavor and a reasonably low level of sodium. In a complex dish like beef chili, good chicken broth helps to prevent an imbalance between the umami-boosted beef flavor and the other flavor enhancers.

One of my favorite beverages is a robust, hop-ladened, English ale. Over the years I have used it as a flavor booster in many recipes. In this recipe, however, it contributed a bitter undertone that overshadowed the bright flavors of other ingredients. I discovered that an American-style lager, like Budweiser, did more to complement these flavors. Unlike the heavier ale, it enhanced the brightness of the tomatoes and onions instead of forcing them into the background.

Chocolate: Semisweet chocolate adds another complex flavor to the stew. I chose Ghirardelli semisweet because it is an excellent chocolate and is sold in thin, 8 oz. bars that are easily chopped.

Meat: Experience has taught me that ground meat, of any kind, is not suitable for a slow-cooked chili. Extended cooking leaves ground meat dry and tasteless.

My first choice of meat for this recipe is center cut beef chuck diced into chunks that will cook up tender and juicy. Beef chuck, in my opinion, is the most flavorful and reliable cut of beef for a slow braising application, and it is a beef cut that is always available in supermarkets. I’ve also found that, like ground meat, most of the other stewing beef cuts dry out during the 90-minute slow braise required for this stew. So, stick with the chuck.

Sweeteners: By design, a pot of chili contains some sharp, acidic flavors which can be moderated with the addition of a small amount of sweetener. For this recipe I chose dark brown sugar. Brown sugar is a simple mixture of sugar and molasses. The molasses adds another level of flavor to the stew, and the sugar adds sweetness that reduces the acidic undertone of the stew.

Umami cocktail for chili: Selecting ingredients for this component of the chili was not as simple as I first thought it would be. I discovered that this mixture could be overdone. My first attempts to incorporate various umami blends into the chili were just that overdone. The increased beefiness of the stew upset the balance of the spices and other more subtle flavors. After applying several mixtures with disappointing results, I settled on a simple combination of soy sauce, anchovy paste, and salt pork. If you have any objections to salt pork, it can be omitted with little loss in flavor. As an alternative to the soy sauce/anchovy paste/salt pork mixture, a teaspoon of soy sauce mixed with an equal amount of tomato paste also works well.

It is time to put my theory about what makes a great chili to the only test that matters. Let’s head to the kitchen and start cooking.

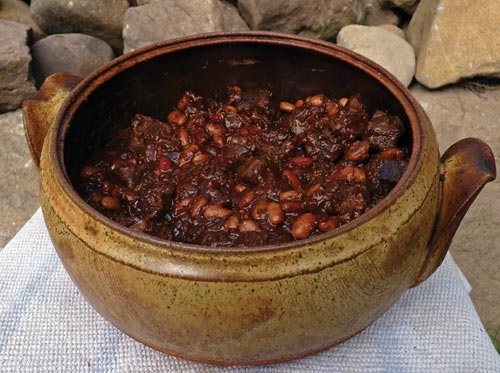

Chili ready for the oven

Chili ingredients:

2 qts. cold water

1½ Tbsp. table salt

4 oz. dried pinto beans

4 cloves fresh garlic, pressed through a garlic press

½ tsp. anchovy paste

1 tsp. soy sauce

2 Tbsp. brown sugar

¼ cup chili seasoning (Spice Islands commercial chili powder is a good substitute if you don’t make your own chili seasoning.)

2 to 4 dried de árbol chile peppers, stemmed, seeded, and torn in half

1½ Tbsp. masa harina (preferred) or regular or fine-ground cornmeal

½ oz. semisweet baking chocolate, chopped fine

1½ cups low-sodium chicken broth, divided

1 large Spanish onion, coarsely chopped

1 to 3 fresh serrano chile peppers, stemmed, seeded, and diced ½ inch

2 lbs. boneless chuck, excess fat removed and cut into ¾-inch pieces

about 1½ tsp. of freshly-ground black pepper (for rubbing the beef)

3 Tbsp. vegetable oil, divided

12 oz. American-style Lager beer. I use Budweiser

1 can (14-oz.) diced tomatoes, drained

½ oz. salt pork, rinsed of excess salt

Method:

1. Combine the water, salt, and beans in a suitable heavy-bottom sauce pot or Dutch oven and bring to a boil over high heat. Remove the pot from the heat, cover, and let it stand for one hour. (This is one method of brining the beans. The other is to cover them with salted water and let them sit in the refrigerator overnight.)

2. Arrange the oven racks so that the pot with the chili can cook in the lower third of the oven. Preheat the oven to 300º F.

3. Drain the beans, rinse well in cold water, and drain again. Set the drained beans aside.

4. Combine the garlic, anchovy paste, soy sauce, and sugar in a sauce dish and set aside.

5. In the bowl of a food processor, combine the chili seasoning, dried de árbol chile peppers, masa harina or cornmeal, and chopped semisweet chocolate. Process until peppers and chocolate are well ground. While the processor is running slowly, add ½ cup of broth. Process into a smooth paste and transfer this mixture to a small bowl. (Do not wash the processor bowl, yet.)

6. Place the onion in the empty processor bowl and pulse until roughly chopped. Add the serrano chile peppers and process to the consistency of chunky salsa. Transfer this mixture to another small bowl and set it aside. (Now, you can wash the processor bowl.)

7. Pat the beef dry with paper towels and rub with fresh-ground black pepper.

8. Heat one tablespoon of vegetable oil in a Dutch oven over medium-high heat until it shimmers. Add half of the beef and cook until the pieces are browned on all sides. Transfer the beef to a suitable-size dish or bowl. Repeat this process with the remaining beef and a second tablespoon of the oil.

9. Heat the last tablespoon of vegetable oil in the now empty Dutch oven until it shimmers. Add the onion mixture, sauté, stirring occasionally, until the moisture evaporates and the vegetables have softened.

10. Add the garlic/anchovy mixture (from step 4) and cook until fragrant, about 30 seconds.

11. Add the chile paste (from step 5), beer, and remaining broth. Bring the mixture to a simmer while scraping the bottom of the pot with a wooden spoon to loosen any brown bits. Stir until all ingredients are well blended.

12. Add the tomatoes, browned beef, salt pork, and beans and stir to blend all ingredients evenly. Return the mixture to a simmer over medium heat.

13. Cover the pot and place it in the oven. Cook for 1½ to 2 hours or until the meat and beans are tender.

14. Remove the pot from the oven and let the chili rest for about 15 minutes before serving. If the chili seems too thick, add small amounts beer or chicken broth to suit your personal taste. (Also, before serving, remove and dispose of the salt pork.)

Good chili is a combination of art and science. I believe this recipe has a balance of both. But I’ve left plenty of room for you to experiment. Give it a try and, if you choose, add some of your own imagination to the formula. Good luck.