By Don Lewis

From Jan. 1 to Nov. 15, 2018, there were 51,898 wildfires across the United States, burning over 8.5 million acres. Despite the commonly held belief that wildfires are predominately a western concern, according to the Insurance Information Institute, every state in the union experienced wildfires in 2017. (To be fair, Delaware’s five wildfires in 2017 only burned a total of six acres, so that state’s loss was less than my pasture.) Nation-wide, insurance actuarial studies have shown that up to 4.5 million American homes are at risk or high risk of damage or destruction by wildfires, and in the last 10 years, wildfires have caused billions of dollars in damage and taken the lives of hundreds.

Roughly 90 percent of all wildfires are caused by human activities. Lightning has never been the chief cause of wildfires. The Camp Fire in 2018, which largely destroyed the town of Paradise, California, was likely the result of a downed power line. Another 2018 wildfire in Utah was caused by a ricochet from a target shooter’s bullet.

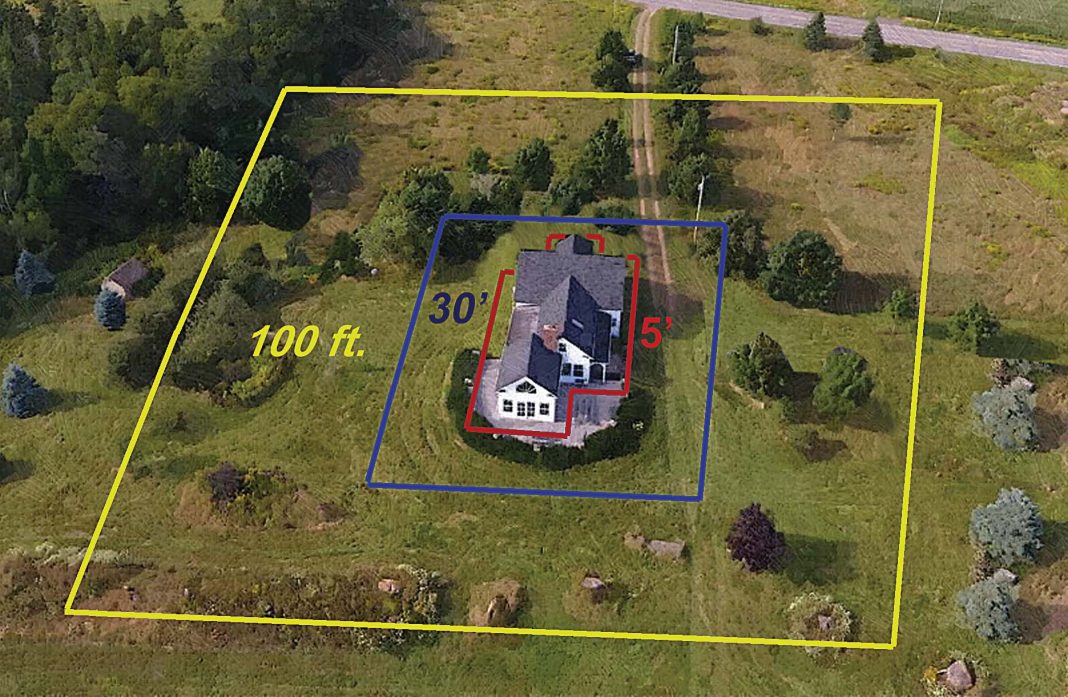

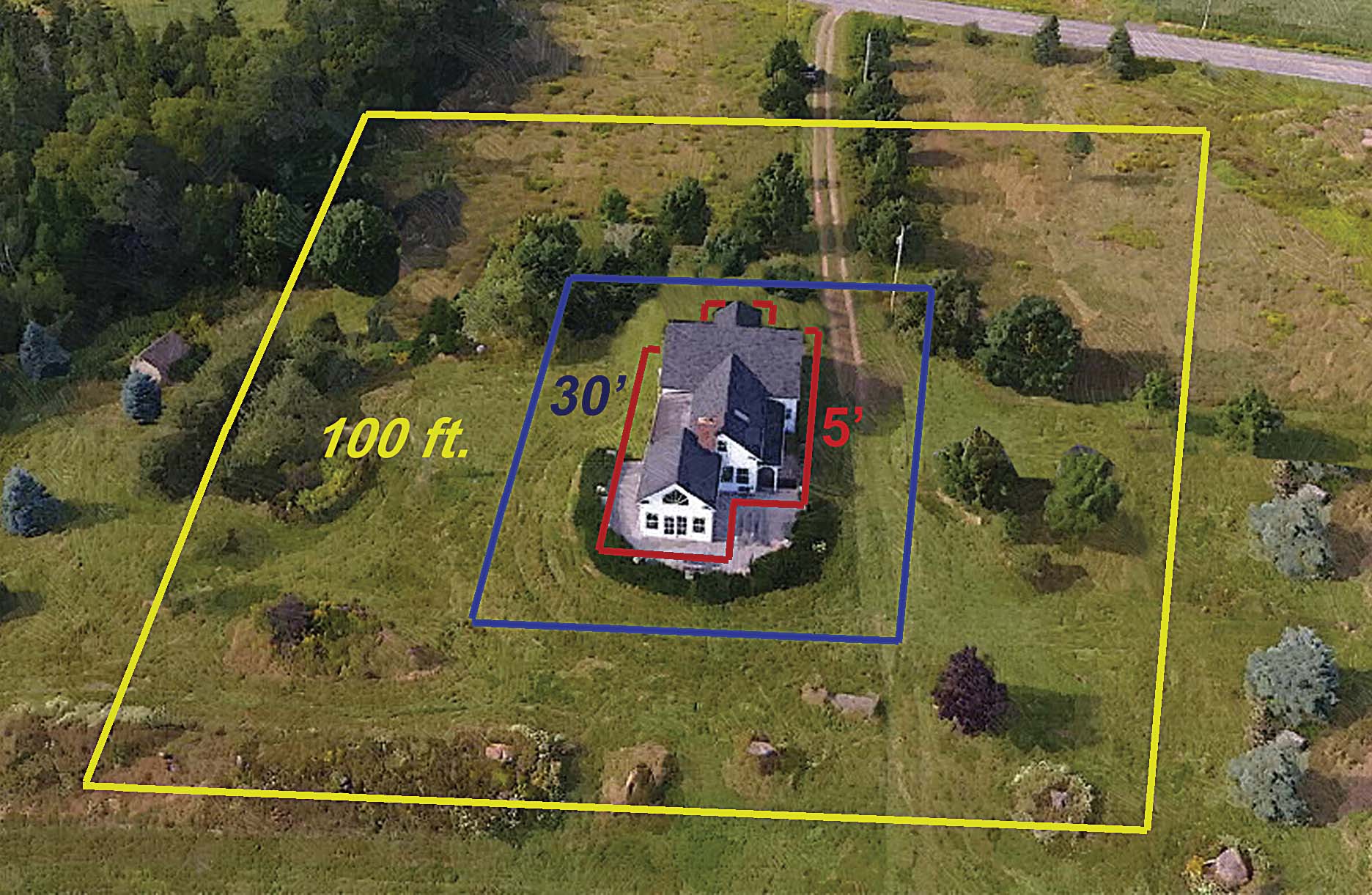

Maintaining a non-combustion zone around the house and landscaping with fire-resistant vegetation out to a distance of 100 feet helps prevent a fire from getting near enough to a structure to ignite it.

Whatever the cause, fires are perhaps the greatest danger to the homes and properties of those of us who live off the interstate and pursue self-reliant living. And while most of us who live (or want to live) beyond the city lights are aware of the wildfire home defense recommendations promulgated by organizations like the NFPA (National Fire Protection Association), even adhering to these guidelines doesn’t keep thousands of backwoods homes from burning each year.

However, there are additional steps that rural homeowners can take that will markedly increase the odds of returning to your property after a wildfire and finding your buildings still waiting for you. Advances in technology have produced many professionally installed and do-it-yourself ways to safeguard homes and buildings in the event of a catastrophic wildfire. This article will describe some of these systems, their advantages and limitations, and (where known) their costs to install and maintain.

The Wildland-Urban-Interface

Fires happen everywhere, and on a total dollar basis, damage and destruction of residential units is obviously far highest in urban settings, if for no other reason than that’s where most people live. But this article is directed specifically at those homes that are located in what is nebulously referred to by fire professionals as the wildland-urban-interface (WUI). I say nebulous, because fire experts consider that interface to exist not only between where your lawn ends and your woodlot begins, but also where the outskirts of a suburb smacks up against a state park.

Those of us who already live in a WUI are therefore often confused; because for many of us, the nearest “urban” setting in one direction might be more than an hour’s drive away, and what we’d consider to truly be “wildlands” might be just as far in the opposite direction.

Specific WUIs can be located in many different variations in topography or vegetation. A WUI can be located between a ranch and a range of high desert chaparral. You can live in a WUI consisting of a log cabin and steep slopes of heavy timber. But while the setting may change, certain conditions are common in most WUIs. Because of their distances from urban centers and their low population base, firefighting assets are few and far between. Therefore, it is far more incumbent upon the residents of WUIs to be proactive in protecting their own homes and properties from wildfires, particularly in the early stages of such fires or when those fires have outrun the professional firefighters.

The embers generated by a fire can be carried aloft more than a mile ahead of (or behind) an active fire on winds generated by the fire itself.

Passive and kinetic wildfire protection

For many years, we rural dwellers had to be satisfied with having control over only one of the two broad ways of protecting our homes and outbuildings in the event of a wildfire. These two categories (in my opinion) can be best be described as passive and kinetic (or active). Passive practices are those construction steps taken by home builders initially — and property owners retroactively — in anticipation of wildfires that haven’t yet occurred.

These practices can include fire-resistant building construction, or retrofits such as metal roofs or fire-resistant siding materials like fiber-cement siding, stone or brick. Fire resistant and retardant paints can also be applied to more flammable home sidings, decks, and fences; and installing one-eighth inch or smaller screening on roof or soffit vents can protect structures from attack by embers.

It also means those passive things that can be done by the homeowner, such as keeping your firewood storage facilities separated from the house by at least 30 feet, creating mini-firebreaks with the careful placement of paved or rocked driveways, maintaining a five-foot-wide non-combustion zone immediately adjacent to structures, and landscaping with fire-resistant vegetation out to a distance of 100 feet.

These and other passive practices are extremely important, because numerous studies conducted by the U.S. Forest Service and the NFPA have demonstrated that high-intensity wildfire flames located further than 100 feet from a house, regardless of that’s home construction materials, are largely incapable of igniting that structure by radiant heat. If you remove or strongly limit the combustible materials from around your home or structures for 100 feet or more, and you build or refit your structures with low-combustion materials, you’ve effectively ended the danger from a wildfire being able to directly approach and ignite your home.

So that takes care of the problem, right?

Not so fast, you latter-day pioneer. Unfortunately, it isn’t the direct fire-to-building contact that’s the usual culprit in wildfire destruction; it’s the embers or firebrands that are lofted into the air from high-intensity wildfires. These firebrands can travel more than a mile ahead of (or behind) an advancing wildfire front. And it’s these airborne embers that are largely responsible for most of the devastating structural fires in the WUI. A single ember that lands in your gutters, or blows into cracks in your siding, or drops in wind-deposited debris against your building, can mean the end of your house.

Look around your home. Where does organic debris concentrate? Here’s the thing: That debris (such as tree leaves, pine needles, or duff) is concentrated there for a reason. These are the areas around your buildings where wind dead zones exist. These areas are not only potential sources of fuel, but are also spots that airborne embers will likely congregate as well. It’s not the radiant heat from a wildfire located 100 feet from your house that’s the problem. It’s the ember-blizzard that most people should fear.

While screen-protected vents, ember-tight construction, and non-flammable or fire-resistant surfaces can help defeat ember-blizzards, it’s the active or kinematic methods of wildfire mitigation that provide the extra crucial layer of protection that can make the difference.

Until fairly recently, kinetic methods of fire protection were largely beyond the abilities of the average home or property owner. In this instance, “kinetic” means increasing the potential for structures to survive an eminent wildfire by the timely application of water, fire retardants, liquid/chemical fire barriers, or heat shields to physically enhance a structure’s survivability from a specific and time-sensitive event.

In the past this was usually done by professionals — assuming, of course, there were sufficient firefighters available to do the job. Even with thousands of professional firefighters from across the nation attacking the 2018 Camp Fire in California, over 1,800 structures were still destroyed.

But today, it’s possible for the individual homestead owner to provide that kinetic protection. However, before we start that discussion, here are a couple of disclaimers:

- None of the following fire mitigation products or services is endorsed by the author of this article nor by this magazine. This includes specific products or services mentioned by brand name or installation firms. The author admits to owning one of the products described in this article, but has never tested it (and hopefully will never need to). Variations of each of these products abound, so search out these variations to determine which products best suit your needs.

- None of the products mentioned in this article are intended to provide enhanced survivability for people. All of the product manufacturers, vendors, and installers strongly agree with this statement. Assuming the use or application of any of these or similar products will allow you to safely remain in your home or buildings when they are overrun by a wildfire is insane and will likely result in your death, even if your house survives you.

Retardants and suppressants

Generally, every external fire mitigation product falls into one of two categories: retardant or suppressant. Some products combine both categories. In general, a fire retardant is a chemical treatment that slows down the oxidation potential of an otherwise flammable material. An example of the use of retardants is the chemicals used in the production of flame-resistant clothing.

Long-term fire retardants can remain effective for many hours, days or even weeks after application. Most retardants slow or stop the spread of fire or reduce its intensity as a result of chemical reactions that reduce the flammability of fuels or delay their combustion. That’s great, except materials that have been treated with a retardant do not put out a fire that’s adjacent to them. And if that fire continues to burn long enough, any untreated material below the surface or zone of retardant treatment is still susceptible to ignition.

Suppressants, on the other hand, stop a fire from burning. A typical example of a fire suppressant is a fire extinguisher. When a fire brand (ember) comes into contact with a fire suppressant, the ember is extinguished. Suppressants generally have a much shorter effective life when compared to retardants.

Both types of products have their benefits and drawbacks. Regarding wildfire treatment or dispersion, both systems usually share one thing in common: almost all the products suitable for home fire defense require water as a carrier for application. Water by itself is an excellent example of a suppressant, and a number of homeowner-operated wildfire protection systems use water exclusively.

Water-only systems

Water-only systems have a certain number of benefits, the most obvious being that you don’t have to buy any added chemicals (some of which can have a fairly short shelf-life). Another benefit to a water-only fire suppressant system is that it’s the least likely to do any lasting environmental damage.

But there are a couple of potential problems with using a water-only system. The first is that water-only-systems have no real residual retardant effects. As long as sufficient water is being sprayed against your house, embers and brands that manage to find their way to your home will be quickly extinguished. But the moment that water is no longer being applied to your home, the suppressant benefits quickly evaporate — literally. Many WUI residences receive their water from pumping their water from wells or springs. These pumps not only move the water, but do so at sufficient pressures for home use. But pumps need power. For those homeowners who get their electricity from the grid, that can be a big problem because power grid failures or intentional utility disconnects during a wildfire are practically a certainty.

Many homeowners like the idea of a water system because it’s easily possible to make one yourself from off-the-shelf PVC pipes and commonly available sprinkler heads. You can find a number of examples and plans of these DIY systems on the internet. If you have a protected power source like a secured generator and a consistent water supply like a high-yield well, pond, tank or even a swimming pool, a DIY home wildfire protection system might be a good fit.

But remember a couple of things before you decide to go this way. Your water-only fire protection system must be full coverage. All of the surfaces of the building you’re trying to protect must be kept wet, and those surfaces must be kept wet especially during those times when the wildfire or air-borne firebrands are present (wetting down your house with garden hose prior to evacuation will be of little use). And your buildings must be ember-tight. Having a completely wet home exterior won’t do you a lot of good if a wind-carried ember can slide inside under an incompletely closed garage door.

In a water-only system, unless you have some way of automatically starting your system at the approach of firebrands, you’ll have to leave your system running continuously. One company that professionally manufactures such a system requires over 6500 gallons of water for 2.5 hours of continuous operation on a standard size home. Furthermore, you’ll have to make sure that your consistent water source will remain consistent during a wildfire (your year-round stream might end up being clogged by fire debris, effectively shutting off your water supply). And your pump power supply will need to be protected as well. If you install a generator to provide pumping power, that generator must be kept safe from embers; and the filters on the system must be sufficient to protect the generator air intake from clogging as a result of airborne particulates created by the wildfire.

Professionally installed water-retardant systems

Many professionally designed and installed systems work around the shortcomings of continuous-spray operation by installing infrared detectors which activate their systems when flames approach a protected building or property. Just how effective some of these sensors are at detecting embers is less certain. Additionally, many of these designed systems are set up to operate on a solar or grid rechargeable battery bank or propane driving protected generator. Companies like waveGUARD™ or Colorado Firebreak™ and Consumer Fire Products Inc. can also supply water tanks, and typically add fire retardant to the water so that even if the water is depleted, the applied retardant remains in effect.

Some of these systems can also be activated by phone. Real-world experience shows these systems do work, but they’re not cheap. Even a modest system installation can easily cost over $20,000, and more extensive systems covering multiple buildings can run into six figures.

DIY fire suppressants

For those of us WUI residents with more modest budgets, less expensive options can be found from companies like Barricade International, Inc. and Fire ETC. These firms and others offer home treatment products designed to be applied by the homeowner in advance of a wildfire.

Barricade International Inc. sells a kit consisting of four gallons of Class A fire-retardant gel. The company estimates the gel, when applied through an included mixing applicator nozzle attached to a garden hose, will treat 2,000 to 2,800 square feet. Barricade Gel™ was invented by a Florida firefighter who noticed while fighting trash fires that used, wet disposable baby diapers simply didn’t burn. Combining water absorbent polymers similar to those found in the diapers, he developed a fire-suppressant gel by mixing those polymers with water. The combination of mixed polymer and water created multiple layers of water-filled micro-bubbles that adhere to surfaces and act as a fire suppressant. When applied, and under normal conditions, the suppressant will remain effective for 8 to 24 hours. The manufacturer also states that the gel can be rehydrated at any time by lightly misting it with additional water. Barricade gel is currently being used by the Los Angeles City Fire Department. The four-gallon kit with applicator costs around $550.

Homeowners can build a water-only fire protection system from off-the-shelf sprinkler heads and PVC pipes, but it will require an uninterrupted source of power and water to function.

Another similar product in Thermo-Gel, described by its manufacturer as “highly effective in fighting active fires, wild land fires, prescribed burns, urban interface fires, aviation applications, and in the protection of all types of structures from homes to commercial and industrial investments.” A basic Thermo-Gel kit is very similar to the Barricade product, consisting of four gallons of concentrated gel and an applicator nozzle. The manufacturer says the kit will effectively treat up to 4000 square feet of surface area. The Therm-Gel kit can be purchased at various sites on the Internet for around $400.

However, there are a couple of things to note about both products. To correctly apply the suppressant gel to your building surfaces requires a minimum of 30 psi water pressure, so if your power or water supplies are lost, neither product may be deployable. Also, while these products have been proven effective, they must be applied prior to the arrival of the wildfire while still leaving sufficient time for the homeowner to evacuate. Additionally, the effectiveness of either product is only good as long as the gel-polymers remain hydrated. Unlike water-borne retardants, once the suppressant foams dry out, they will no longer either extinguish flames or impede combustion. The manufacturers of both Barricade Gel and Thermo-Gel provide a three-year shelf life warranty.

Fire suppressant gel kits are available which the homeowner can spray onto the exterior of their home ahead of exposure to a fire. The kits include several gallons of concentrated gel and an applicator, but typically require a hose with water pressure of at least 30 psi.

Fire shields

Well okay, maybe all of these companies’ services and products listed seem intriguing, but you simply don’t have sufficient capital to install a multi-thousand dollar system. And maybe, like many of us who live here in the hinterland, your consistent power and water capabilities are sketchy. There’s another possibility out there offered by companies like Firezat™ that you might want to consider: a fire shield.

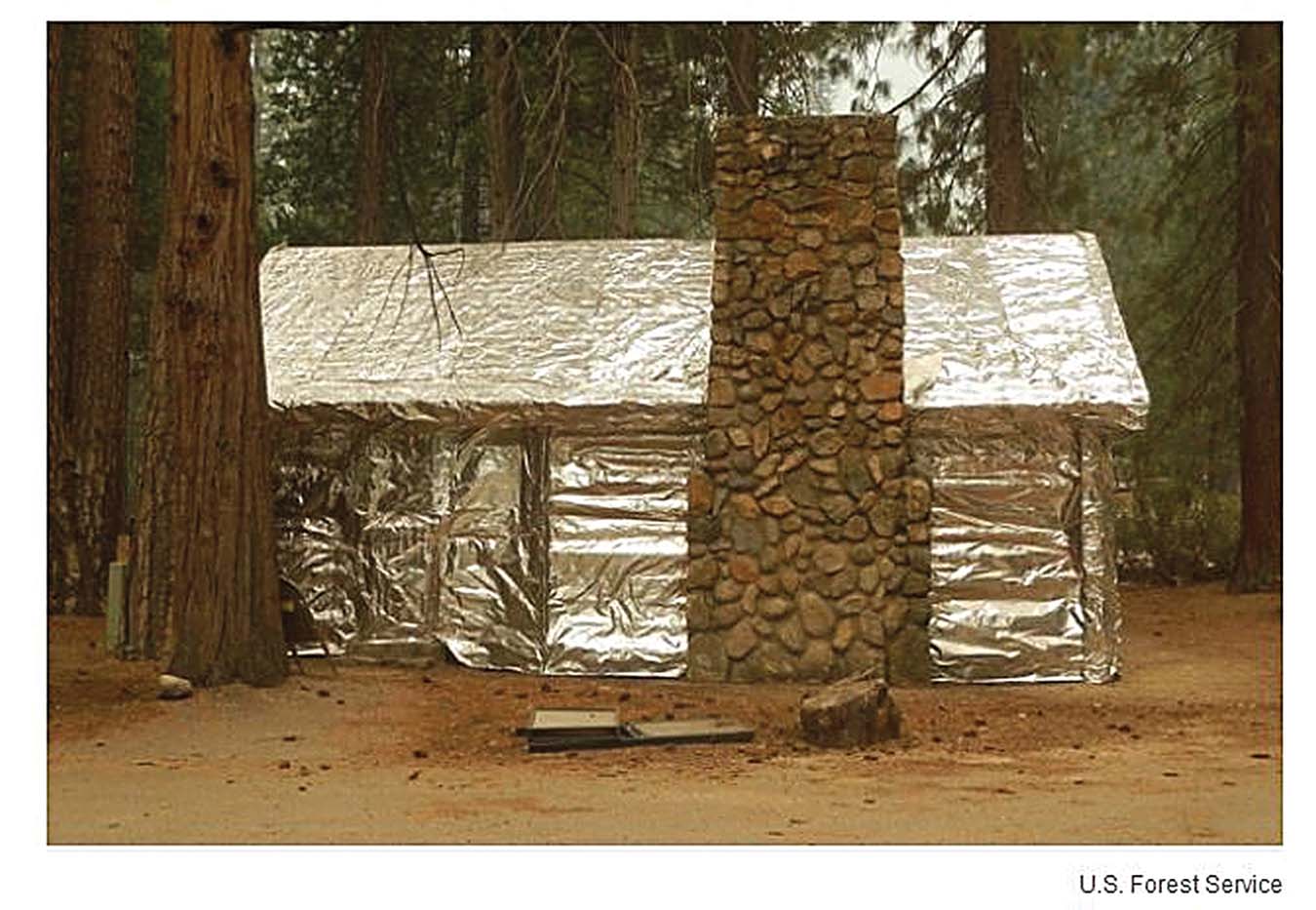

Firezat and similar firms sell rolls of fire-resistant aluminum fabric which can reflect as much as 95 percent of radiant heat away from structures, as well as providing a barrier that can keep burning embers from lodging against your building.

These products have been used by the U.S. Forest Service and other governmental agencies to protect historic buildings in remote areas where ground crew firefighting would be difficult. The aluminized fabric is used to cover the entire building. The sheets of fabric are held together and in place by staples. In its literature, Firezat claims most structures can be covered in as little as an hour by two or three people. Some of the studies conducted by the U.S. Forest Service have indicated this claim may be a bit optimistic. Nevertheless, tests conducted by the company show that even direct flame-to-fabric contact over untreated wood keeps the wood from reaching a flash ignition point (about 585°F) One roll of Standard Duty Fire Shield will cover around 1,200 square feet and can be purchased for around $750.

A fire shield, such as this aluminum fabric, can reflect most of the radiant heat from a fire and also keeps embers from entering crevices in the building.

Private “firefighters”

Lastly, you may have access to a professional wildfire protection service without even knowing it. Many national insurance companies like AIG, Chubb, USAA, and Nationwide offer WUI homeowners specific wildfire loss mitigation services usually as a complimentary policy service or an additional premium service. Recent sensationalist California wildfire articles with headlines like “Wealthy’s use of private firefighters ignites debate in wildfire country” either gloss over or completely ignore the fact that in almost all cases, it’s not the rich who hire these private “firefighters,” it’s the insurance companies. And the use of the term “firefighter“ in those click-bait headlines is a bit misleading as well.

Wildfire Defense Systems, Inc. (WDS), a firm headquartered in Montana, is the largest of these “private firefighters.” Company literature states, “WDS firefighters have the same training and certification as government firefighters. All WDS firefighters are trained and certified under the National Wildfire Coordinating Group (NWCG) same as Federal and most of the State firefighters in the nation.” WDS says over 90 percent of the homes and properties they service for nearly a dozen national and regional insurance companies are of average value (meaning, these services aren’t just for the wealthy).

With regards to these services, AIG a national property insurance firm’s own website states their “Wildfire Protection Unit® is not a private fire department; it’s a loss mitigation service designed to pre-empt damage well before a wildfire even ignites.”

Most of the services offered by wildfire loss mitigation services like Wildfire Defense Systems, Inc., Firebreak Protection Systems, Inc., and Zone 1 Wildfire, LLC are educational. Personnel from these and other fire mitigation services will visit the properties of policy holders and provide advice and instruction on property modifications and improvements to better resist wildfire damage. Many of these companies will also send rapid-response teams ahead of a wildfire to treat policy holder’s buildings with fire retardants.

Not all insurers offer these services, but a lot do. However, many insurance companies who do so also do a poor job of making their policy holders aware of these services, so it’s a good idea to contact your insurer and inquire about any wildfire mitigation programs they may have available. If you’re in the market for insurance for your new residence in the wildland-urban-interface, you might consider the availability of such services in the selection of your insurer.

Wildfires are a fact of life for those of us who live in the WUI. Recently, a better understanding of wildfire dynamics and new advances in firefighting methods have made it possible for the individual backwoods home owner to play a much greater role in protecting their property in the event of a wildfire. And since self-reliant living is what we’re all about, anything that we do ourselves to better protect our chosen way of life is only natural.