My parents lived through the Roaring Twenties and the early Thirties when “motor bandits” and assorted gangsters were always in the headlines. I became fascinated with the era hearing them discuss it in the 1950s, when the “Dillinger Days” were closer in time to them than 9/11 or the Columbine High School atrocity are to us now. Having researched the period and written about it rather extensively, I was familiar with the work of Girardin, Russell, Helmer, Matera, Mattix, Burroughs, Toland, etc. When “Gangster Hunters” came out this year, I leafed through it quickly and left it on the bookshelf. At first glance it appeared to be just a rehash. But when my discerning friend Greg Ellifretz mentioned he was reading it, I figured it deserved another chance. I’m glad I bought it.

Yes, a lot of the content will be familiar to students of the era, but there are some nuggets in it. For instance: We all know that legendary Texas Ranger Frank Hamer, along with local sheriff Henderson Jordan (a relative of famed gun guru Bill Jordan, one of my personal mentors) were responsible for taking down Bonnie (Parker) and Clyde (Barrow) in Louisiana. But did you know (I didn’t!) that Federal agent Leslie Kindell was the one who learned that Bonnie and Clyde’s minion Henry Methvin had recently moved to Bienville Parish and his father, Ivy, was willing to trade the deadly duo for leniency for his son? It was he who hooked up with Hamer and Jordan and set the ambush/capture plan into action.

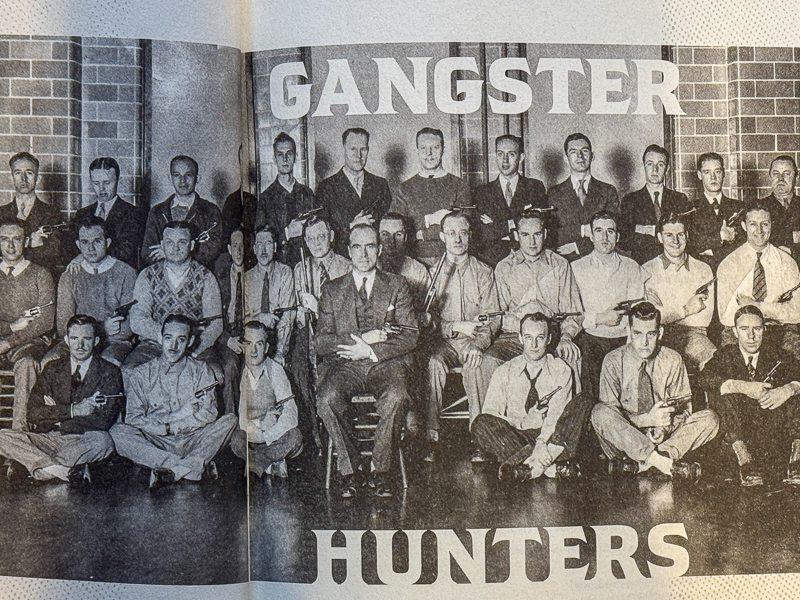

The book begins with a grainy picture of a class of FBI agents seated together and apparently pointing their Colt .38 Special revolvers at one another, all but one with their fingers on the triggers. Firearms safety protocols weren’t the same then.

Author John Oller does not come across as a gun guy. He describes the Colt pistol John Dillinger was trying to deploy when he was killed in Chicago as a .38 when records show it was a .380, a common mistake particularly in those days. But overall, he has done an excellent job on his history of the period. A new student of the era could do a lot worse than to start with Oller’s “Gangster Hunters.”

In author John Oller’s defense, .38 equals .380, mathematically speaking.

In firearm terms, they are not the same, but if he’s not a gun guy we can probably overlook that mistake.

A possible alternative explanation: it might be his editor(s), if not himself, who missed a simple typo. Missing letters are a common typographical error, especially if while proofreading the manuscript, as previously stated, the two numbers are mathematically equivalent, and not something the brain will instantly and intuitively recognize as an error.

Excellent comment.

Actually, the .380 is .355 while the 38 is .357. I always thought this was marketing but I looked it up to reply to you and discovered the reasons lie in the development history of the two cartridges.

Interesting times back then. Criminals who wore suits and carried more powerful guns than criminals use today, and a justice system that actually tried to prosecute them.

Trigger finger discipline and muzzle awareness were not much of a thing back in the day. Many of the photos seen of WWI and WWII troops show them with fingers on the trigger and muzzles pointed everywhere but in a safe direction. These days you even see pictures of the Taliban with fingers straight and outside the trigger guard. The rate of hunting accidents back then was also horrendous when compared to modern times.

On the other hand, the 12#trigger on a DA revolver must have helped prevent NDs a bit.

Mark,

Good points. A wonderful development is that accidents with children and guns have also decreased. Thank you, Eddie Eagle.

I expected to hear of more gun accidents after the George Floyd buying spree, but I haven’t heard of any. Maybe the new gun owners just bought guns, and put them under their beds. Or, hopefully, we really have seen people learn to be safer around guns than they were in the past.

If Dillinger was carrying a pocket pistol, it may have been a .380. He was known for carrying a 1911 in .38 Super.

Yeah, when your blog email opened I couldn’t even read the copy until I had enlarged that picture and looked it over closely. Just WOW!

Regarding firearms safety a few generations ago (especially during WWII), group photos of U.S. military personnel in the field commonly show them pointing their firearms, many of them machine guns, at each other with their fingers on triggers.

While I’ve never come across any research and data on that dangerous custom, I suspect there were more than a few negligent discharges and casualties.

I don’t know when Rule 3 style trigger discipline was first formally taught by the military or police academies. But I suspect that some people who were serious about avoiding NDs figured it out on their own.

I *have* seen a couple of WW II photos showing troops keeping their fingers outside their trigger guards, in one case a guy with a BAR and in the other someone holding a 1911A1 .45. And I *seem* to recall one showing a German soldier with a Browning Hi-Power.

I made at least one typographical error. Can I edit this?

I think I fixed it for you, any other typos? E.P

History is a fascinating subject. There are many stories from the old west that got embellished a little as time went on, and when it came time to adapt to the modern, motorized world crime and crime reporting adapted as well. J. Edgar knew what needed to be done to get the modern FBI funded and up and running! https://mileswmathis.com/dilli2.pdf

Comments are closed.