| Issue #125 • September/October, 2010 |

We planned it to be permanent, well built, and able to withstand the extremes of temperature, humidity, and weather a greenhouse must tolerate inside and out for many years. It would be big enough to grow plenty of food, an easy place to work, and adaptable to our changing needs. We live in a harsh climate and wanted the greenhouse to extend our growing season in both early spring and late fall.I do not have a green thumb. The only plants I have any luck with are the ones that can be sawn into boards. My wife has two green thumbs, maybe three. She can grow anything. In our early life together she would, in her shy way, ask me to build helpful garden projects and, in my busy way, I would half pay attention to her requests. After years of doing these half-asked projects we decided a full-fledged greenhouse would be included in our next home.

The investment in such a project is considerable, and building it as a separate structure is the conventional way to go. However, we decided to make it an integral part of our home after researching the advantages of an attached greenhouse.

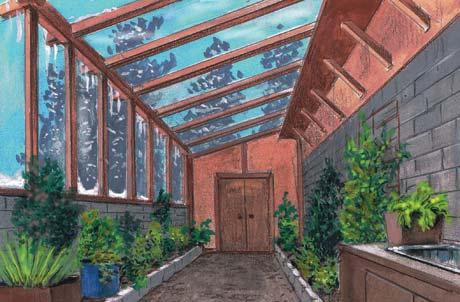

We built ours 50 feet long and 9 feet wide, 450 square feet in area and about 3,000 cubic feet in volume. It is attached to the south-southwest wall of our home. There are three doors, one into our house and one on each end wall. Screened vents and lots of glass make up the south-facing wall. It has lived up to our expectations. In fact it has an extra advantage. Guests love it. My wife, Jen, can entertain them for hours out there if they are fellow green thumbers. She has shyly asked that I hang a hammock from the ceiling, but so far I am only half listening to that request.

|

Ours is a solar greenhouse, and we live in the north country. Even so, the only slow growing time is from late December to early March when even cool weather crops sometimes need to be covered. On a frigid but sunny day the greenhouse warms up and the plants are happy. Seedlings started in the house are moved to the greenhouse in early spring until it is time to plant them outside in the garden. In late fall Jen brings some garden plants back in to extend their production time.

All summer the greenhouse produces vegetablessome that normally grow in a much warmer climate and others I’m not sure grow anywhere else on this planet. Jen is really good. Plus she grows flowers and herbs with names I can’t pronounce.

|

From my perspective as a builder there was another very important benefit for adding this addition to the house. It is a serious source of heat for our home. The sun shining into the greenhouse warms it quickly, even on a cold day. Opening the connecting door lets heat pour into the house for hours. How much heat? We have a 3000 square foot house. We heat it with four or five cords of wood, which covers about half our heating requirement for the year. The greenhouse, with help from the windows above it, supplies the rest. Wood costs around $250 per cord this year. That is a saving for us of $1000 to $1250 this winter.

In addition to food and heat, the quality of air in our house is healthier. If you know about the good effect a dozen house plants using up carbon dioxide and releasing oxygen has on an interior space, imagine how much better it must be with a few hundred plants.

The passageway between the house and greenhouse has a screened door and a solid door. This doorway along with two small vents (with covers) between the greenhouse and the main house control air circulation.

I can think of more good reasons to build a greenhouse onto the side of a house. In addition to gaining food, heat, and fresh air, having a new source of entertainment, and saving on fuel costs, we spent less on materials and labor by building against the side of our home than had we erected a four-sided freestanding greenhouse. Easy access to the home’s electrical and plumbing systems for the greenhouse during and after building was a significant bonus too.

The range of skills needed to build a project such as this are very much like those needed to build a house. If you don’t have all of them you could contract out the foundation, wiring, plumbingwhatever mystifies youbut much of it you can do yourself. Plan accordingly.

The first decision to make is where to attach the greenhouse. If you are building a new house and can orient it as you please and have the greenhouse be a part of the construction process, you are very lucky. Most of what I write about here is for adding a greenhouse to an existing home, but there are ideas for everyone.

The south wall is the most obvious and best location, but if, like our house, the walls do not align perfectly north, south, east, and west you must chose the best you can. We built on the south-southwest wall because it was the longest, had the most exposed foundation, and best exposure to the sun. We discussed the possibility of a wrap-around greenhouse, but decided the slight extra sun exposure and cost did not support it. Your situation may be different. Perhaps a true south-facing corner on a small house would call for a wrap-around. Be aware, it is possible to build a greenhouse that is too big. I’ll say more about this later.

Look at what you have to work with on the chosen side of your house. If you have a full cellar, are there small windows? Perhaps a bulkhead? These make good access points and would help with air circulation between house and greenhouse. Most cellar walls come up out of the ground a foot or two and extend down into the ground six or eight feet. This makes it possible to pull the earth away from the foundation and have the greenhouse floor several feet below outside ground level to provide more volume, frost protection, and better sun penetration, using the home’s cellar wall as a heat sink and the excavated earth as a berm around the outside of the greenhouse. Use the advantages available to you.

Now look at the wall of your home above the foundation and consider how high up to attach the roof and sidewalls of your greenhouse. Slightly below existing windows is a good location. Just above the windows is another. Slightly under the roof overhang is possible too.

As you can see in the picture of our greenhouse project, we chose the first option because we had so much foundation wall available and lots of windows we did not want to block. Most homes have one or two windows and perhaps a door on the chosen wall. Building onto the home above those would be the best strategy to give you easy access to the greenhouse and plenty of circulation potential.

|

Build the foundation

After taking all the details into consideration and drawing up your plans, it is time to start the first part of the project, and that is the foundation. Of all the parts of your greenhouse, the foundation is the most important if you want it to be permanent and strong…just like your house.

You may choose to have a contractor do this job. You need a poured concrete or block wall down below frost line with a good footing. It is a lot of work. I hand dug a ditch four feet down to bedrock and built a concrete block wall from there to two feet above grade and filled all the cores with rebar and concrete. I also embedded threaded lag bolts in some of the block cores for securing the plates of the walls that would be built on top. I added a one-inch layer of Styrofoam board against the outside of the walls plus a dry-laid stone wall against that, as you can see in the pictures. It took a lot of work but I was young and ambitious then.

This foundation wall is under all three sides of the greenhouse addition. It isolates the earth inside, holds some heat, and keeps out frost and animals that like to dig tunnels. A lot of fragile glass is dependent on a solid, stable foundation. Do a good job.

While the foundation is being built is the best time to remove the old earth inside the greenhouse footprint and replace it. We had sand as fill around our house foundation when it was built. In the greenhouse footprint, we dug some of that away and left some for a base, then added Jen’s special soil mix on top. If you are using the services of a contractor with an excavator, have them remove the old dirty dirt from the greenhouse floor and pile in fresh, wholesome, plant-friendly soil at this time. It will save you a lot of hard work.

This is the time to attend to any utility items that need to be buried. In our case, the main sewer pipe runs from the house through the earth of the greenhouse, through the foundation wall, and out to the septic tank. I had to work around that, but I put it to good use by installing a laundry sink in the greenhouse and hooking the drain into it. The sink has been very useful. A working greenhouse really needs an area with a sink, counter, and shelves.

I don’t recommend burying wires in the greenhouse, but if you must, be sure they are protected inside some tough metal or plastic pipe. Be sure to put a notice up on the wall with a map indicating where they are located.

We had some ideas about a drainage system under the greenhouse soil but eventually decided it could be added later. It was never put in and has not been missed.

Okay, the foundation walls are done, the soil is in place, and it is time to build the main structure. Prepare the house wall by removing the siding to expose the sheathing in the area where the greenhouse will be attached.

Planning the shape of the greenhouse depends largely on the glass you are going to use. In the pictures and drawing you can see the three sections of our addition: the lower window wall resting on and bolted to the foundation wall, the slanted big windows making up most of the ceiling, and the roof that is attached to the house wall. The actual dimensions of your greenhouse will be custom designed for the materials, size, and area involved in your project, so my how-to advice is meant to give you ideas and methods to use rather than exact plans.

|

The window wall

I hate buying new glass. It is expensive and there is so much excellent pre-owned glass available cheap or free for the taking that I look for that first. I used some double-hung, double-glazed windows from my stash for most of the front window wall. They were installed on their sides with the screens in place. They work as windows and vents, plus they lock. Those and two large plate glass panes, all framed with 2x6s, make up our lower window wall. The bottom plate of the window wall is bolted to the foundation with the lag bolts mentioned earlier. The top plate is a 2×6 topped by a 2×8.

Next, I partially framed the end walls in order to securely brace the window wall, leaving doors and other details to be added later. This gave me a masonry wall about 5½ feet from bedrock to about 2½ feet above ground and 9½ feet out from the house wall. The house wall was exposed to a height of about 8 feet to just below the house windows.

The roof deck

The next part of this adventure is building the roof. It is actually a narrow deck extending out from the house wall. Mine is about 30 inches wide and runs the length of the greenhouse. This roof deck has a number of advantages. It is a handy work platform while building and makes the exterior upkeep of that whole wall above it, and washing all those big windows, less complicated during the life of the house.

The roof deck must be very sturdy. I framed it with 2x6s and decked it with ¾-inch plywood. It is bolted through the house wall studs every four feet and supported with knee braces every 35 inches. I insulated it with R19 fiberglass and protected the underside of it with a layer of 6-mil vapor barrier plus a layer of blue poly tarp.

The roof deck keeps heat from escaping at the highest part of the greenhouse. The underside of the roof deck is where I wired some pull chain lights and GFCI outlets. It is a good place to hang potted plants, something for plants to climb on, or possibly even put up a hammock. Like I said, build it sturdy.

If you have been careful with your measuring and building and have not indulged in too much spontaneous construction, your lower window wall will be perfectly aligned horizontally and vertically with your roof deck so the rafters that connect them will all be exactly alike, fit perfectly, and accommodate the big windows to be installed on top of them.

|

Finding cheap glass

I want to take a paragraph or two to let you in on a way to find the best glass ever for a greenhouse. The ones we used are 34″ x 75″ tempered glass. Of all the sizes of tempered glass available, that is the most common because it is used in sliding glass doors and those window walls you often see where people have a view, a deck, a swimming pool, or whatever, to gaze upon while sipping martinis. What’s more, all those windows are double paned for insulation.

Sadly for them, lucky for you, those double-paned windows lose their seal after a few years in the hot sun or by getting bumped too often. A fog then builds up between the panes and they must be replaced. When you find these fogged windows you get a two-fer. Take them apart (not easy, but worth it) and you get two excellent seventeen-square-foot panes of very tough glass.

You can track down a number of these fogged windows by visiting your nearest glass dealer who may have some out back, or they can tell you which contractor has recently bought the most new windows of this size. Find him and make an offer on the old ones. I did this once and got 18 (count ’em x 2) fogged windows free just for hauling them away.

You can find them at junk shops…excuse me, Architectural Antique Shops. Try the dump…or rather, Transfer Station. Ask around. I once found a supply of tempered glass this size at a mobile home supply store. They were rejects from the factory (there was a rather pretty rainbow stain on each one) and I had to buy a whole pallet, which cost me $100. There were 150 panes of glass, each weighing 28 pounds. The store guy kindly forklifted the pallet onto my pickup truck, which nearly had a stroke getting them home. I did a lot of glass jobs after that, one of which was the much-too-big greenhouse I built in my enthusiasm of getting such a good deal.

If you must buy new glass, the 34″ x 75″ dimension is readily available and often the least expensive because more of those are made than other sizes. Use single thickness panes of tempered glass for a greenhouse. I’ll tell you why later on. Avoid Low-E glass. It doesn’t let IR (infrared) light waves pass efficiently through it and you want those light waves in your greenhouse.

Tempered glass is amazing stuff. I have dropped it off a roof, had rocks fall on it, and shaken it like a sheet. It is flexible and tough. Its Achilles Heel is the edge. If you tap the edge with metal the whole pane shatters to pieces. Be aware of this as you handle the glass.

|

Ceiling rafters

Now let’s deal with those rafters between the lower window wall and the roof deck. I am going to show you a way to build these rafters differently than my originals. I woulda, coulda, shoulda done it this new way but you can learn from my experience.

Plan the spacing between centerlines of the rafters. My glass was 34 inches wide. I want a 1-inch space between the panes. So it will be 35 inches between the centers of my rafters. Be very accurate about this 35-inch measurement as you build. Note: my knee braces under the roof deck line up with these rafters.

Here is the difference between my old way and the new improved version. Way back then, I used single 2x6s as rafters. It worked, but not very well. They were too narrow. I recommend you use doubled 2x6s or doubled 2x4s as rafters. That means the top of the rafters will be three inches wide and provide an ample supporting surface for the glass panes while leaving a one-inch space between them.

You may think more is better and consider using larger sized rafters but don’t. The rafters create a lot of shade early and late in the day so bigger is not better. Doubled 2x6s or doubled 2x4s are strong enough. Of course, use the best quality lumber for these rafters. Get good straight ones with few or no knots.

Cutting the rafters to size takes good carpentry skills. There are angle cuts on each end and the dimensions have to be very accurate. When I have to make multiple identical parts like this I very precisely cut the first one and use it as a template, or pattern, for all the rest.

When you double up these rafters, make sure they are securely attached to each other with screws. In fact, use screws for attaching the rafters to the rest of the building too. Screws resist the push and pull of strains on the structure much better than nails, and if something needs changing or fixing later, screws are easier and neater to extract and reuse. I recommend galvanized screws for their rust-resistant quality.

Before attaching the rafters, cut a piece of 90# rolled roofing 18 inches wide, and drape it over the whole length of the 2×8 top plate of the lower window wall. This covering will drain rainwater away on the outside and condensation away on the inside. This is an important detail. Without it, rot will develop easily in this area. Don’t ask me how I know.

Before attaching the rafters is also the best time to finish the end walls. Look at the drawing. The end walls are a filled-in version of the cross section of the green house. I framed mine with 2x6s, sheathed the outside with ½-inch plywood and my special split shake siding, installed R19 fiberglass insulation between the studs, stapled a 6 mil vapor barrier over that and attached an inside wall covering of 5/8-inch OSB. All that was built around good, solid, well-fitted, weather-stripped doors with screen doors. We did not want bugs, air leaks, or the opportunistic deer and raccoons around here getting in and eating the polifloxis and gernimoniums…or whatever.

I also added 16×16-inch screened vents with solid weather-stripped wooden doors near the ceiling in each end wall. One of the vents has a built-in fan controlled by a temperature sensitive switch that starts the fan when the interior temperature of the greenhouse hits 85 degrees. I did this because our greenhouse sometimes decided it wanted to be a sauna and pushed the thermometer we keep out there beyond its 140-degree limit on hot summer days.

With insulated end walls and roof deck, a foundation wall with foam board against it, and the house foundation and wall for backing, you have a pretty well-built house addition that can hold heat. Now let’s build the solar gain part of the greenhouse.

Screw the rafters into place, resting the lower ends on top of the window wall plate covered by 90# roll roofing and attaching the other ends to the face of the roof deck, as shown in the drawing. Make sure the rafters are square with the window wall and the top edge of the roof deck. Sight across the rafters as they are put into place, making sure they are even with one another, which they should be if you were careful and accurate during construction.

|

Installing the glass

Now you have a place to mount all those tempered glass windowpanes. Our greenhouse has fifteen of them. Before setting them in place, take care of the following details:

Attach a layer of ice and water shield to the top surface of your rafters. It comes in rolls of various widths. Use the 4-inch-wide stuff. That will give a half-inch overhang on each side for extra protection. I used 90# rolled roofing all those years ago, but that was a primitive time before this new material was available. The ice and water shield is much better. It provides a soft surface for the glass and prevents leaks.

You will need a crosspiece between the rafters at the top ends, flush with the top edges of the rafters, to support the upper edge of the tempered glass panes. Put that in, using screws, and cover it with ice and water shield, which should be continued up onto the roof deck a few inches.

Let’s review. You have built an insulated foundation wall with a window wall on top, roof deck, end walls, installed the rafters, and have a waterproof, soft surface ready for your tempered glass panes to rest on. Here is how they should fit.

Each pane of tempered glass should sit on the rafters one inch in from the edges and one inch onto the upper support piece. The lower edgeand this is very importantshould extend beyond the lower window wall’s 2×8 plate by one-half-inch, just barely resting on the water-shedding 90# rolled roofing covering described earlier.

I know…sounds crazy to let that vulnerable edge of tempered glass hang out there in space, but the risk is worth it because all the rain, snow, and ice will slide right off and prevent wandering moisture from rotting out the wood of your lower window wall.

Given the low angle of the glass ceiling, the tempered glass panes can sit in place temporarily without sliding off but they need to be clamped down. Cut some ¾” x 3″ x 75″ knot-free boards. Using galvanized screws, screw the boards into the rafters, clamping the glass edges in place. I used four evenly spaced screws per board. That one-inch space between the panes lets you drive the screws in without hitting the glass if you are careful. I put a ½” x 3/8″ thick piece of weather stripping on the underside edges of the clamp boards to further pad the panes of glass and was very gentle with the torque I applied to the screws. The tempered glass is tough, but that was tense work. I used a screw gun and did the final tightening with a hand screwdriver.

Okay, the glass is installed and now it is time to cover the roof deck. I used 90# rolled roofing and still would today, but underneath it I would use a wide layer of ice and water shield. Run both the ice and water shield and the 90# rolled roofing up the wall of the house a few inches and clamp it there with a batten or run it up under the siding to prevent leakage. It is a tricky place to waterproof, so be extra meticulous in your work.

|

The lower edge of your 90# roofing material (but not the ice and water shield) should overhang the upper edge of the tempered glass panes and clamp boards by two or three inches. Don’t seal the 90# roofing to the glass panes. Someday you may have to replace a pane of glass and this will make it easier and avoid damage to the roofing material. Do use plastic roofing cement to hold the 90# rolled roofing in place on the roof deck. Avoid using roofing nails.

Here’s another tip I learned from experience. Rainwater pouring off our house roof, then six feet down onto the roof deck caused accelerated wear of the 90# roofing material. I had to install a gutter to catch the rainwater and spill it off to the sides. This presents an opportunity to catch thousands of gallons of rainwater and one of these days I will take advantage of that situation. If your installation needs it, put the gutters on sooner rather than later.

I worried that the tempered glass panes might slowly move down the roof in the hot sun despite the board clamps. Hot sun can do thisI have seen it. I attached some positive stops at the lower corners of the glass where two panes come together.

First I screwed ½-inch thick spacer blocks to the lower window walls out to the edge of the panes. Remember, the panes overhang by a half inch. Then I screwed on some galvanized metal plates as positive stops. I protected the glass by putting some tough plastic U-channel around the glass where it met the metal. Now the board clamps hold the glass down and the stops keep the panes from sliding down the wall.

And that’s about it. You have your greenhouse up and running. Of course there are other details to consider and here are a few:

Our 15 panes of tempered glass did not exactly take up the full length of the greenhouse. I had to make up the difference with a roofed section to reach and cover one end wall. This was good because any little mismeasurements in the structure can be corrected or compensated for here. Be sure to build it like the roof deck with insulation, roofing, and vapor barrier.

The foundation wall of our house was exposed to plenty of sun coming through the glass ceiling. To make it a better heat collector I painted it dark green. Black might work better, but it would be too depressing.

In summer you cannot have too much screened vent area. In winter you don’t want any. We have about 16 square feet of screened vents, including the one with a temperature-controlled fan, plus two screened doors that are each 17 square feet. That ratio (50 square feet of vent per 3000 cubic feet of volume) works well for us.

|

We have two screened vents and a screened door to exchange air between the house and greenhouse. It is wonderful. Any mixing of air between these two parts of your home will bring you much pleasure.

I recommend that all your electrical wiring be exposed. In a workspace where nails or screws are going to be driven hither and yon you want to be sure you can see any electrical dangers.

Expose your plumbing too. Provide a way to completely drain the supply plumbing in your greenhouse. There will be times when it gets cold enough to freeze pipes. Somebody will forget to do the draining. I won’t mention names. PVC or CPVC (plastic) plumbing pipes and fittings are much easier to install and repair than copper pipes.

We get snow, lots of snow. I use a big push broom to pull the snow off the greenhouse glass after a storm. It is surprising how well snow insulates. When the snow comes off you can see the temperature rise very quickly inside the greenhouse on a sunny day.

There is one bit of magic we discovered with our greenhouse. I thought that the single panes of glass in the ceiling would need some sort of covering on cold clear nights to prevent heat from radiating through the glass and off into space. To our surprise we found that the rather moist air in the greenhouse forms frost on the underside of the glass ceiling on cold nights, preventing heat from radiating out. In the morning the sun melts the frost and warms the place all day. Because of this effect we decided not to put a woodstove out there, as we had considered doing, and have not missed it at all.

Nasty bugs once invaded our greenhouse when Jen brought in some plants of dubious origin. It required clearing the space of all plants and a thorough delousing of the place. Sounds traumatic. It was, but doable in a controlled area, and your greenhouse should be very well controlled with good doors, solid walls, and tight construction. Be very careful what you allow into your greenhouse. This experience reinforced the need for well-maintained screens in every opening.

Pollinating plants is a bit of a problem in a greenhouse where insects can’t do the job for you. One lady we heard about had a beehive built into a side wall of her greenhouse. The bees had access to the greenhouse and the outdoors. Brilliant. And she got some honey.

I have built greenhouses as integral parts of two of our homes and they have been so successful that I would do it on any home I lived in. It is a big job but worth the time and investment. The advantages in food production and heating more than make up for the cost of the addition in very few years. Increased self-sufficiency in these uncertain times is a good reason to consider attaching a greenhouse to your home. Being able to walk out into a summer atmosphere during winter is a very pleasant benefit too. A disadvantage is that Jen is looking through her catalogs for a hammock.

I have built a greenhouse that has my basement door connecting to the 3-story house. I am trying to learn about the venting required and also the best application or not of a vapour barrier on the un-glassed walls?

Fabulous, I think we are going to build/have built- one just like it- off your discription! Will keep u up on it?

Great read! Very thorough, informative, helpful and comical. I will be adding a greenhouse to the construction of my new house but this was still great information!

We want to do this but unsure if iris feasible for a doublewide Redman home. What do you think?