|

|

| Issue #101 • September/October, 2006 |

The year was 1873. Samuel Colt had invented the revolveror at least introduced it to Americain 1836. The Colt Navy .36 and Army .44 cap-n’-ball revolvers had been the primary handguns of the Civil War, and had proven themselves the dominant cavalry weapons of that conflict. Smith & Wesson had leapt ahead of Colt’s Patent Firearms with the Rollin White patent for the self-contained cartridge. That patent had now run out, and Colt was not going to let its arch rival take over the market. Colt now offered the world a new revolver. Sam Colt had passed away, and one William Mason was the new gun’s designer.

Colt called it the Model P. It was quickly adopted by the United States Army and became the Single Action Army, or SAA in gun-enthusiast shorthand. In caliber .44-40, Colt called it the Frontier Six-Shooter.

|

The world at large came to know it as “the Peacemaker.”

If you grew up in the 1950s and ’60s, and ever played “cowboys,” you probably had a Mattel Fanner 50-cap pistol that was cloned from the Peacemaker. Pausing briefly for WWI, Colt produced the original gun from 1873 until the beginning of WWII. After the second great conflict, the company determined that the design was obsolete and not in demand, and let it die. But, in the early- to mid-1950s, a spate of TV Westerns featuring the Colt six-shooter brought a new surge of interest. A young entrepreneur named Bill Ruger, who had started a gun company in Connecticut in 1949, decided in 1953 to bring out a copy of the famed “cowboy gun” in .22 caliber, and called it the Single-Six. It was followed by the Blackhawk in .357 Magnum (1955) and .44 Magnum (1956). A new company called Great Western was formed exclusively to create copies of the old Peacemaker in the mid-’50s, and it was, in fact, a Great Western .45 that James Arness is said to have wielded as Marshal Matt Dillon on the classic TV series Gunsmoke.

Colt woke up and started making them again, in what gun collectors would call a Second Generation. Colt made the SAA in various forms off and on through the rest of the 20th Century and through the present third generation, currently produced at Colt’s Custom Shop with a hefty price tag. In recent years, the sport of Cowboy Action Shooting truly rejuvenated these old-time six-guns. Italian companies like Armi San Marcos and Uberti began duplicating these and many other firearms of the old frontier, at reasonable prices. Today, the market is full of them.

An original Colt is still a pricey thing, and you can expect to pay well into four figures for an original First Generation Colt like the Frontier .44-40 I got for $150 along with a Colt Police Positive revolver thrown into the deal by the seller back in the 1960s. They are excellent investments. The best news is, there are many fine clones available for reasonable prices. These include Ruger’s Vaquero series, recently downsized from its heavy .44 Magnum frame to a more manageable “original Colt” size; the very nice Beretta Stampede revolvers manufactured with superior quality control since Beretta’s purchase of Uberti a few years ago; and the latest low-priced, high-quality bargain, the Gaucho series from Taurus of Brazil.

The allure of the Peacemaker

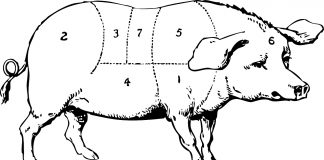

These revolvers are gate-loading single actions, and as such were obsolete before the 19th Century turned into the 20th. “Gate-loading” means that cartridges are inserted one by one through a cut-away exposed by a flip-out gate at the right rear of the cylinder. Live cartridges or spent casings are ejected through the same portal, with a finger-pushed ejector rod mounted in a housing offset on the right side of the gun’s barrel.

Single action means that the hammer has to be manually cocked with one or the other thumb before the trigger will fire a shot, and this has to be done for each and every shot. A fast “cowboy shooter,” holding the gun and working the trigger with the dominant hand and cocking the hammer with the support hand thumb in a two-hand hold, can shoot one of these old-time revolvers as fast as a modern double-action revolver, which needs only a pull of the trigger for each shot. When firing one-handed, thoughthe way half or more emergencies requiring reactive use of a handgun end up happening, it seemsthe single action just can’t keep up with a modern double action.

Since the 1890s, Colt and S&W and similar double-action revolvers have had swing-out cylinders from which all six spent casings can be ejected with a single push of an ejector rod. With the cylinder swung out of the gun, all six cartridges can be reloaded at once in a double-action revolver if the shooter has a speedloader or a moon-clip device to hold all the cartridges together in a single unit.

|

Let’s put the difference in reloading time into perspective. Plucking cartridges one by one out of belt loops or dump pouches, cops from the 1930s onward were able to meet a demanding standard that the FBI developed during that period: Draw, fire six shots double action, reload, and fire six more, all in 25 seconds from seven yards, the distance FBI had established was the average for gunfights back then. This became much easier in the 1970s when speedloaderswhich had actually existed in the late 1800sbecame popular among police and armed citizens. Give me a good double-action revolver and full moon clips or Safariland Comp III speedloaders, and on a good day I can do that drill in only six seconds. And if that seems fast, consider this: The record, held by Jerry Miculek, is 2.99 seconds for those same 12 shots, all hits, with a Smith & Wesson Model 625 .45 revolver, reloading with a “moon clip” that holds all six cartridges together.

By contrast, today or at any other time period, it took a true master shooter to make the 25-second time with a single-action, gate-loading Peacemaker or equivalent. That’s how long it took to punch each spent casing out of the cylinder and reload each of the six chambers one at a time.

But today, you still see single-action frontier-style revolvers worn by traditionally minded people ranging from working cowboys to ordinary folks who just like living in the back country.

Part of it is tradition.

But there is more than tradition at work there…

The backwoods rationale of using the single action

There are several rationales for using the single action in the backwoods. The least of these, but still on the radar screen, is the fact that the large frame models are more rugged with heavy handloads than double actions. Back in the 1950s, the great outdoorsman and gun expert Elmer Keith wrote that he had determined the Ruger single-action Super Blackhawk to be a stronger .44 Magnum than the only double action then available in the caliber, Smith & Wesson’s Model 29. The first .454 Casull revolver, a crushingly powerful weapon, was the superbly crafted five-shot Freedom Arms, a gun designed faithfully in the single-action, gate-loading Peacemaker style.

A more important reason for some was cost. A friend of mine who won many honors on the Alaska State Patrol calls the Ruger Super Blackhawk “the official Alaskan handgun.” People who go fishing or hiking in bear country there are in truly deadly danger from the big brown bruins, and when the .44 Magnum came out in 1956, the double-action Smith & Wesson cost in the $120 range, but the Ruger single action had a $96 price tag. To this day, the top quality single action is less expensive than the equivalent quality double action, most brands for most brands.

I would submit that there is a much better and much more practical and tactical reason why so many people who live in rural America choose a single action as their “backwoods gun.” They are not particularly concerned about self defense against human predators, and should that come up, they are not terribly disadvantaged in having a powerful, reliable revolver at hand that only holds a few rounds. Most man-against-man gunfights are over with less than six rounds fired, anyway.

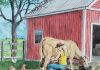

No, it’s because even today, the modern backwoods dweller rides horses. Rides snowmobiles. Rides all-terrain vehicles. And that person may have to fire the handgun from that moving platform to save his or her life.

And, when you’ve had to fire a single action revolver from a moving platform such as that, it is not going to fire a second time by accident. It can’t possibly fire again until you intentionally thumb its hammer back to prepare it for the next shot.

|

Let’s think about it. You are the typical horseman, whose mount is not accustomed to gunfire. Suddenly, that fox that has been at the henhouse comes into sight, or you see a feral dog chasing your livestock. The handgun comes out of your holster. You take a sight picture, you press the trigger, and…

BANG!

Depending on the caliber, the handgun’s report explodes not terribly far from your horse’s ear, at something between 100 and 140 literally deafening decibels.

Is the horse likely to shy? Oh, yes.

You have one hand on the reins and one hand on the gun. As the horse rears violently, throwing you off balance and destabilizing you, your non-dominant hand desperately convulses on the reins. You have just fired a shot an instant before, so the trigger finger of your dominant hand is on the trigger of the handgun.

Physiologist Roger Enoka long ago scientifically determined how certain natural human movements under stress cause accidental discharges of guns in hand. There is interlimb response: As one hand closes on something, the other hand closes sympathetically, and…BANG. There is postural disturbance: As we start to lose our balance, we move convulsively to regain it, and our muscles sympathetically tighten, and …BANG. There is startle response: Something startles us and makes us jump or convulse. The gun is in the hand; the finger is on the trigger; the flexor muscles that close the fingers are stronger than the extensor muscles that open those fingers, and…BANG.

It is very likely to happen with a self-cocking semiautomatic pistol. Even if the trigger has come forward on a double-action revolver or semiautomatic pistol that might take 12 or more pounds to activate, the average human hand can close its fingers with far more pressure than that, and a person who is in shape can exert the equivalent of their body weight on the hand dynamometer, or hand-strength gauge. Autoloader or double-action revolver, in that situation, you will hear…BANG.

But with a single-action, frontier-style Peacemaker or equivalent revolver, you will hear…nothing. Because the gun’s design is such that it cannot fire until the thumb has performed the deliberate movement of cocking the hammer again.

Does this sound far-fetched? If it does, you haven’t talked with some of the backwoods people I’ve talked with. I know men who have had to shoot snakes and such from horseback. Even when the horse is supposedly “broken to gunfire”that is, trained not to rear up and panic at the sound of a shotnone of that training encompasses getting the horse used to the thing that may have triggered the shot. In other words, you can train a horse to ignore gunfire. You cannot train the horse to ignore the striking rattlesnake or the lunging mountain lion that has caused you to draw and fire your gun in the field instead of in training.

Is it far-fetched to think someone might have to fire from a moving snowmobile, mountain bike, or ATV? Perhaps. But then, I have not been chased by a pack of wild dogs while astride a bike, a horse, or a snowmobile. For those who have had that experience and have had to fire to protect their lives, a gun that won’t “go off by accident” as they struggle to regain control of their “mount” doesn’t seem far-fetched anymore.

How to shoot a single-action revolver

The first thing you need to know about single action revolvers is, don’t carry them with a live round under the hammer. Load the six-shooter with five cartridges and leave that last empty chamber under the down-at-rest hammer and the firing pin.

For a century, Americans understood this. You didn’t leave a live round under the hammer of a single-action revolver because it could go off if dropped or struck. Historians say that happened once to Wyatt Earp. Where does that leave the rest of us “lesser gunfighters?” Don’t leave a standard-shift car parked on a hill in neutral without the parking brake engaged, don’t put a live round under the hammer of the single-action revolver you carry, don’t eat the yellow snow. These were good, logical rules of life, well understood by people who had common sense.

Unfortunately, as the 20th century wore on, common sense became less than a common trait. People forgot the old wisdom and the old ways. Stupid people killed and crippled themselves and others when they dropped their six-guns that were loaded with all six shots and the predictable and terrible BANG! was heard. Gun companies were sued.

Led by Ruger, the gunmakers who produced single-action revolvers came up with floating firing pin designs that used a transfer bar mechanism and allowed modern SAAs to be carried safely with all six chambers loaded. The problem that followed was one of habit: If we got used to carrying one single action with a live round under the hammer, we realized, we could transmit that habit to others.

|

Thus, it has become the mark of the firearms professional that any single-action revolver is to be carried with an empty chamber under the hammer. Engineers may consider it redundant safety practice. Anyone with common sense calls it “the belt and suspenders approach.” Firearms professionals call it “the rule.”

My gun safes at the moment contain two old-style Colts that would discharge if dropped on the hammer with a live round under the firing pin, and oneColt’s much more recent Cowboy modelthat won’t. They also contain Beretta/Uberti, Ruger, and Taurus single actions that are mechanically drop-safe with all six chambers loaded. In my hands, all of those revolvers will be carried with an empty chamber under the hammer. End of story, end of safety lecture.

Now, let’s talk about shooting this kind of handgun, and shooting it well.

If you can get both hands on the gun, use the dominant hand on the grip-frame and the dominant index finger on the trigger, and the thumb of the support hand to cock the hammer. This is far faster and more efficient than asking one hand to do all the work and the other to just go along for the ride.

You want to have a firm hold on these guns. They have a slow lock time. In firearms parlance, “lock time” is what elapses between when the trigger pull is completed and the firing pin starts to move forward, and when the cartridge in the firing chamber actually discharges. As the photos show, these guns had big, heavy old hammers to be sure they had enough impact to light off the percussion caps of the muzzle loaders and then the early-generation primers of the old black powder cartridges the Model P was originally designed for in 1873. Those hammers come down with a clank that can actually move the gun if it isn’t held firmly, not the click of the lighter hammers of more modern double-action revolvers. The heavier the impact of the falling hammer, the more disturbance to aim. This is why Peacemaker-style revolverseven Colt’s Bisley model, named after the famed international shooting range not far from London, England: Bisley Campwas obsolete as far as target shooters were concerned very early in the 20th Century.

If you look at the accompanying photos, you’ll see what has become known as the “plow handle” grip shape of the frontier-style single-action revolver. It was designed to mitigate the discomfort of recoil by letting the gun “roll up in the hand” when the shot went off. They do this very well, and it has made generations of heavy revolver shooters more comfortable in terms of “kick” with single-action .44 Magnums instead of double-action versions. However, it also slows down recovery time between shots because the gun has to be repositioned in the hand before the next shot.

In my mid-teens, shooting my modern Ruger Blackhawk .44 Magnum and my antique Colt .44-40 Frontier Six-Shooter, I figured out that if I curled my little finger under the butt of the gun, it wouldn’t roll up in my hand. The recoil pattern didn’t hurt me that much more, it just changed to where the whole arm lifted in recoil instead of the gun lifting in the hand. However, the relationship of gun to hand remained constant, and allowed me to get back on target and thumb-cock that Peacemaker-style revolver for the next shot much more quickly.

I was pretty proud of myself for figuring it out, until I read Elmer Keith’s classic book Sixguns that was written in the early 1950s and showed the exact same technique. Turns out that Elmer learned it from the old cowboys he knew in his own youth in the early 20th Century…and they had learned it in the 19th. All I had done was re-invent the wheel.

|

Know how to safely load and unload your “cowboy-style” revolver. With that gate-loading system, only one chamber at a time is visible to the operator of the gun. It requires your immediate and total attention. Slowly rotate the cylinder around twice, six plus six, to make sure that every single chamber is empty.

When you are loading, to guarantee that an empty chamber comes up under the hammer when you’re done, with most single actions you want to follow the protocol developed in the American West in the last quarter of the 19th Century, the original heyday of this gun. It goes like this:

Load one cartridge. Rotate the cylinder past the loading gate until an empty chamber has gone by. Then load four more. This should bring the one empty chamber up under the hammer. Then lower the hammer on that empty chamber. With the hammer all the way down on that empty “launch tube,” the action is locked and a loaded chamber can’t rotate up “by itself.” The old cowboys called the protocol “load one, skip one, load four.”

Always double check visually! Looking in through the side of the gunuse a flashlight, if you’re manipulating the revolver in the darkyou’ll be able to see the space between the rear of the cylinder and the back part of the frame in which it sits, which is called the cylinder window. You will see the rims of the cartridges in five of the chambers, and you should be able to see the empty space, indeed the empty rear of the chamber, at the back of the cylinder under the hammer. If you are absolutely certain that you are seeing this, then things are as they should be, and you are safe.

To free up the cylinder to make it rotate so you can load and unload, the original Colt SAA and most of the clones require the hammer to be drawn back to the half-cock notch. Modern Ruger revolvers, the so-called New Models, free up the cylinder when the loading gate is opened and the hammer is down in its “at rest” position.

Do you really want a single-action revolver?

|

Let me be plain here. I’ve discovered in three and a half decades of writing that if you say something positive about something, you are seen as endorsing and recommending what you wrote about. That ain’t necessarily so, and that’s true here.

I live in a rural area these days. I don’t carry single-action revolvers. I carry modern semiautomatic pistols and double-action revolvers.

I use single-action revolvers. Sometimes for hunting. Sometimes for cowboy competition matches. Sometimes just for the fun of shooting them.

I do not recommend single-action revolvers for everyday carry, except for the rural person who is constantly on horseback and may have to fire from the saddle. In that situation, and only there, I think the single action may have a place as a constant-carry sidearm. If the “mission profile” of your handgun is geared more toward self-protection, you are better off with something more modern. Slow loading/unloading/reloading time, slow pace of sustained fire if shooting one hand only, and difficulty of quickly and safely checking loaded versus unloaded status all militate against the old cowboy-style gun, and show you why it has so long been considered obsolete by those who go in harm’s way.

What I am saying is, if you’re more concerned about a mountain lion or a rattlesnake when you’re on horseback than a carjacker when you’re on the road, the single action may have an advantage for you if you carry it carefully and safely, the traditional way.

And if you are careful and responsible, and the old ways just feel better for you, and you just feel more comfortable when armed with a single action revolver, you know what?

You’ll get no argument from me.